18 March 2008

Dulcie Holland: Building a Foundation

Image: Dulcie Holland

Image: Dulcie Holland

This month saw the release of the second journal issue in resonate magazine. By re-approaching some of the music composed by Australians in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, the collection of articles provides new ways of approaching old understandings and prompts new questions for future debate. For Rita Crews, President of the Music Teachers' Association of NSW, the legacy of Dulcie Holland is also an important one. While sometimes dismissed as a composer of student works, Holland’s musical output during the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s was prolific, including successful works for film, chamber ensemble and solo instruments. Here Crews reflects on Holland’s career as both composer and writer, and explores the compositional techniques used in Piano Sonata, her major piano work.

Margaret Throsby, in an interview with Laurie Zion on ABC radio, posed the question: ‘When did sounding Australian become OK?’ (Throsby 2007). Whilst question and answer related to British vs. Australian accents and the changes that took place in the 1960s and ‘70s, a similar question can be considered in terms of Australian music, namely: ‘When did acknowledging the work of Australian composers of the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s become OK?’ These were decades that witnessed an enormous compositional flurry with sponsorship provided by various university grants, by the ABC, by banks, musical organisations and festivals. We too readily dismiss this period of time – particularly the 1950s – as a period when composers merely followed trends set decades earlier, instead of seeing it as part of an important part of our cultural background, a foundation to our understanding of the changes that allowed later Australian composers to find their own independent voice.

One such composer was Dulcie Holland (1913-2000), generally dismissed as simply a writer of works for students. Holland was, however, one of Australia’s most prolific and committed composers during the decades in question.

Born in Australia, Dulcie Holland began piano lessons at age six, and in 1929, after completing her education at Shirley School, continued her studies at the NSW State Conservatorium of Music completing both the Diploma course (DSCM) and the LRSM in 1933. Her teachers at the Con included Frank Hutchens (piano), Gladstone Bell (’cello), together with Roy Agnew and Alfred Hill for composition. Her musical development results from a variety of influences including family background and environment, education and training as well as cultural experience, and this multi-faceted training became a crucial factor in the development of Holland’s own harmonic language and musical style.

Dulcie Holland was an inheritor of a period of time when Australian music was set against a backdrop of European, and specifically English, culture and values. For Australian musicians and composers of the ‘Dulcie generation’, serious musical tuition invariably involved overseas study on a permanent or semi-permanent basis, often at a prestigious London institution. Conversely, conservatoria in Australia imported conductors, performers and teachers to fill the positions demanded by such institutions and, in many cases, this practice is still maintained today.

So it was that Holland continued her studies overseas via the obligatory stint in London where she studied composition with John Ireland at the Royal College of Music. During her two years at the College she won both the Cobbett Prize for chamber music and the Blumenthal Scholarship for composition. With the outbreak of WWII in 1939, Holland returned to Sydney. She married Alan Bellhouse in 1940. Marriage and motherhood still allowed her to pursue her career as a prolific and successful composer and recitalist. In 1951 Allan Bellhouse took up an exchange teaching post in London and, with their two small children, the family spent a year in England where Holland studied serialism with Mátyás Seiber. Whilst pleased to explore the method, she had no particular affinity with the technique, rejecting it as a primary means of extending her own artistic expression.

So, what did Holland have to offer to the period under review? Many and varied compositions in a variety of genres, while the substantial Piano Sonata is arguably the most important of her vast collection of solo piano works. Space precludes a detailed analysis of the Sonata1 but the following analysis of its first movement demonstrates various aspects of Holland’s individual harmonic and structural language, because this section of the work encapsulates many of her typical compositional techniques.

Written in 1953, the Piano Sonata is a complex work, cast in the three movements of the traditional sonata model but without traditional key relationships. Around 15 minutes in duration, the work was first broadcast by the ABC in 1953 with the composer as pianist, and in 1992 the ABC recorded a performance of the work by Nigel Butterley. Further recordings were made in 1993 by Tessa Birnie on the Southern Cross label and by Ray Lemond on the JADE label.

The Piano Sonata may be regarded as a spiritual work, described by Holland as ‘good triumphing over evil’, a poetic reference to the moods established by each of the three movements (Holland 1992). The first movement establishes a dark, brooding atmosphere; the second contrasts in style, mood and tonality giving a sense of calmness; and the third movement is bright and cheerful. Holland regarded the Sonata as a ‘mirror to life, which is full of varying moods’ (Holland 1992). This allusion to life can itself be equated with the allusion to key that is found throughout this work. Non-traditional key relationships and swiftly changing tonal centres provide the element of conflict that is expected of a sonata-form movement. It is not until the last movement of the sonata that these tonal conflicts are finally resolved by the use of opposing, yet related keys.

The first movement is in sonata form with the tonal centre of G sharp dominating the harmonic fabric. Individual intervallic relationships between the various motivic strands are structurally important to the overall plan of the movement. A three-bar ostinato arpeggio figure of open fifths built on the tonic and dominant of G sharp, begins the exposition, and appears in the bass for the first 13 bars of the movement. A link between the bass figure and the treble occurs in bar 3, when the ostinato appears in chordal style. This ‘ostinato chord’ also assumes importance later in the movement.

The ostinato introduces the principal thematic material which begins at bar 4. This principal statement, which alludes to the tonality of G sharp, is a combination of two treble linear motives supported by the ostinato figure. The two treble motives, named for convenience, X1 and X2, consist of the following strands:

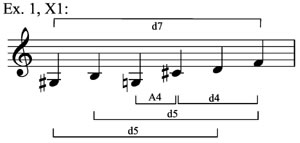

X1: a 6-note figure, appearing in the soprano and alto lines of bars 4, 5 and 6, and distinguished by its use of augmented and diminished 4ths and 5ths whilst traversing an overall diminished 7th:

The supporting ostinato figure of bar 1, which rises by a perfect 5th and descends by a perfect 4th, is linked to the linear movement of X1.

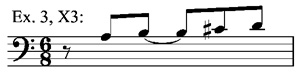

X2: a 3-note figure appearing in the tenor voice of bar 6 and, whilst it involves some chromatic movement, is centred on major and minor thirds:

The ostinato bass and both motives appear in their entirety in the opening of the work and the syncopated rhythm of the principal thematic material adds further interest to the structure of the motives. At times, the theme is interrupted by appearances of the ostinato chord in a technique that Holland employs in the treatment of the ‘Reflective’ chord in the earlier 1942 work, Unanswered Question2. At bars 8 to 10, the principal theme is reiterated and extended by one note to create a tritone; at bar 11 the ostinato chord is twice repeated and the succeeding five bars contain sequential statements of the principal theme. Bars 17 to 21 prepare for the transition. During the course of this first section there is also some prominence given to chromatic movement in the inner parts which serves to obscure the tonality.

The transition material which begins at bar 23 with material derived from X1 creates a shimmering texture of broken chord figuration and an increase in dynamic level. A further rhythmic figure introduced during the transition is linked to the later development section. The last four bars of the transition are homophonic in style, and progress in syncopated rhythm through a series of 7th and 9th chords, to prepare for the succeeding subsidiary thematic material which begins at bar 35 in the tonality of D minor, a diminished 5th above the original tonality of G sharp minor. This theme is clearly related to the principal statement material by a similar melodic figure which is now extended and includes two further motives, X3 and X4:

The theme begins with sequential movement and the supporting broken chord bass line uses the new rhythmic figure derived from the transition. In common with the principal theme, this subsidiary theme is also composed of two strands of material that incorporate the two motives. At bar 40 the melodic strand of X4 is extended by one note to descend by an additional major third which initiates a bitonal passage whose rhythm is derived from the last three notes of bar 40. The passage descends sequentially for four bars (41 to 44) with the tonality of F in the treble, while the bass progresses through the tonalities of D flat, F sharp, D flat and E flat. At bar 45, the subsidiary theme is restored, now in the tonality of A flat, a logical harmonic progression from the preceding passage. At bars 50 to 51, X4 returns in D minor tonality to lead to a six-bar codetta beginning with the dominant 9th of D and then progressing by a series of tonic 7th chords, to cadence on the tonic 7th of G minor. The codetta itself takes an important role in introducing a further thematic area that has its origin in the extended version of X4 that first appeared at bar 40. This descending codetta theme appears at bar 52 and later reappears in the development.

The development itself begins at bar 58, and contains a complex interweaving of the four motives that comprise the material of both the principal and subsidiary themes. The opening tonality of F sharp is stated by way of a chord derived from the original ostinato chord, with a supporting two-voice texture that incorporates a variation of both the ostinato figure and X4. A series of dominant and diminished seventh chords follow, appearing as a trill-like figure, providing decoration to motivic references. Bitonality is also present. Following this section, the tonality of F sharp anchors further references to the decorated version of X4 leading to bar 80 where the codetta theme appears. The tonality of this area moves from C to E flat by means of the tonic triads of C major, D minor, F major, C minor, B flat major and E flat major, arranged as major or minor seventh chords. The bass supplies supporting octave figuration to the chord above.

A one-bar descending arpeggio figure in D flat major leads to the second section of the development (bar 85) which presents both the principal thematic material and the development of X1. This motive, now in D flat major, is supported by arpeggio figuration. X1 then ascends by octave figuration to cadence on F sharp at bar 91. The F sharp acts as the subdominant of C sharp, the supporting tonality to a C major tonic triad in the upper part. A series of descending triads follows to bar 97, supported by the tonic of F sharp. The texture of the last section thins out as the development reverts to homophonic style. A chain of tonic seventh chords, concluding on a thrice-repeated low E, follows. The E acts as the subdominant of B and prepares for the recapitulation that begins at bar 117.

Shorter than the exposition (32 bars compared to 57), the recapitulation is mainly concerned with presenting the subsidiary thematic material in various tonalities, opening with X4 now in B major/minor. Previously, the first appearance of this material had been in D minor. As the first appearance of this motive had been supported by the subdominant of D, it is now supported by the subdominant of B, creating a sense of unity. Further appearances of X4 follow, creating an area of conflict by a bitonal relationship with the lower part: the motif in the top part moves quickly through the tonalities of A, D, and G, while at the same time the supporting arpeggio figure in the lower part moves principally through the tonalities of B, D, B flat and F. At bar 141, as the recapitulation nears its conclusion, the principal thematic material returns for three bars, in a shortened version of its original form, combining both X1 and X2, supported by the ostinato figure of bar 1. The tonality of this closing section is that of A minor with lowered fifth, and the movement ends with the tonic chord of A minor, a minor second higher than the opening tonality.

The second movement is cast in a modal/tonal mixture that forms the harmonic background to a cantabile melodic line. The third movement is a 282-bar toccata in which the development of thematic material, embedded within arpeggiated figures supported by pedal points, is the principal feature.

Many of the compositional techniques used in the Piano Sonata are typical of Holland’s style. Undoubtedly, piano music – particularly student repertoire – is the genre for which Holland is best known, and within this genre she exhibits a range of compositional techniques and styles, often less conservative and more appealing than many of her contemporaries.

In all, Holland’s compositional output includes the background music for some 40 documentary films, many under the auspices of the (then) Australian Department of the Interior, and which are mainly on Australian subjects;3 many vocal and choral works; a large amount of music for chamber ensemble of various instrumental combinations; orchestral music and music for solo instruments and for bands. She won a number of composer competitions then sponsored by the ABC and APRA as well as many awards from other organisations. In 1963 she won second prize in the GMH Theatre Award for her play setting, Jenolan Adventure. Her Symphony for Pleasure is one of many works recorded by the ABC, in this instance by the South Australian Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Henry Krips.

As an author, Holland wrote a large number of music theory textbooks designed to assist students studying for the various Australian Music Examinations Board syllabi. She also shared authorship with her husband in writing several elementary textbooks on music-related subjects that were subsequently used in Australian schools.4 Her period as both an instrumental and theoretical examiner with the AMEB extended from 1967 to her retirement in 1983. In 1977, Dulcie Holland was made a Member of the Order of Australia for her services to music, and in 1982 she acquired yet more formal qualifications by earning a Fellowship from Trinity College (FTCL). To crown her career, in 1993 she was awarded the degree of Doctor of Letters honoris causa by Macquarie University and in 1994, the Fellowship in Music from the AMEB.

Holland’s conventional training stood her in good stead and meant she was well-equipped to expand her skills and to become part of that important cultural background that allowed composers of the following decades to build upon – and whether to accept or reject – the work of the ‘Dulcie generation.’

Holland’s pride in being an Australian composer is evident in her works and her writings. As early as 1937, she stated that: 'the next decade should be an interesting one for Australian composition as Australians are at last beginning to discover their own personality, instead of merely imitating the manners and idioms of other nations (Ceylon Observer 1937).

Music that gives a sense of balance, of confidence, of individuality, of formal structure – music of the decades of the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s – is finding its way back into vogue, acknowledged as being ‘OK’. Dulcie Holland was an energetic and committed composer who contributed much to that period of time when Australian composers were attempting to seek their individuality and lay a foundation for the next generation who were to find a voice that no longer belonged to the culture of a nation on the other side of the world.

Notes

1. For a complete analysis of this work and others by Dulcie Holland see: R.Crews, An Analytical Study of the Piano Works of Roy Agnew, Margaret Sutherland and Dulcie Holland, Including Biographical Material, unpublished PhD thesis, 1994, the University of New England, Armidale. [available from the Australian Music Centre and the author]

2. An unresolved chord – a piling-up of superimposed 4ths on D – that is used at cadences, is varied and transposed 11 times and opens and closes the work.

3. Some of the titles include Channel Country, Edward John Eyre, Paper Run and Pearlers of the Coral Sea.

4. These works were published by William Brooks, Waterloo, NSW and include the following titles: A History of Music for Beginners; Senior School Harmony and Melody; and From Beethoven to Brahms.

References

The Ceylon Observer, 1937, 'Musicians from Sydney,' 19th September [author unknown].

Throsby, M. 2007, Mornings with Margaret Throsby ABC Classic FM, 8th November, 2007.

Holland , D. 1992, Holland’s annotations to a program entitled, ‘Dulcie Holland’s Piano Music’, broadcast by 2MBSFM, Sydney, 8th November, 1992.

© Australian Music Centre (2008) — Permission must be obtained from the AMC if you wish to reproduce this article either online or in print.

Subjects discussed by this article:

Rita Crews is currently President of the Music Teachers’ Association of NSW. With over 30 years teaching experience at the private and tertiary levels, including distance education, she has been an AMEB written examiner since 1988. She has a special interest in the history and analysis of Australian music. Her Honours thesis concentrated on the keyboard works of Miriam Hyde, while her doctoral thesis is an exhaustive analytical study of the piano works of Roy Agnew, Dulcie Holland and Margaret Sutherland.

Comments

Add your thoughts to other users' discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

DH Piano Sonata

by Michael Sollis on 19 March, 2008, 5:05pm

An ensemble I work with performed an arrangement I made of Dulcie Holland's piano sonata, the first movement 'Brooding', as well as an arrangement of a Margaret Sutherland piano piece of the same period in a concert last year.

Both pieces went down well with both the audience and the performers. Interestingly enough, it was the pieces written from this time that got better response than the more contemporary Australian works.

Searching for such repertoire was not easy. I'm sure there are other institutions around Australia that are doing similar things, but it is worth noting that Larry Sitsky has established a very fine resource of piano music from this period at the ANU School of Music, and recently published a book on the subject, which is well worth reading, as it provides one of the few accounts of music from this period.