29 June 2017

Richard Toop - obituary

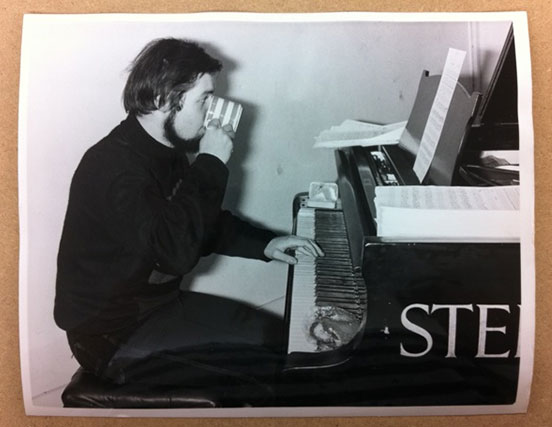

Image: Richard Toop

Image: Richard Toop © Sydney Conservatorium of Music, University of Sydney

Writing about and remembering a person you've lost can be salutary in the days after their death. However, in Richard's case, my urge to remember and celebrate is in tension with his rejection of funerals, memorialising, and the pleasures of nostalgia. He was, after all, the principal musicologist of the tabula rasa, the postwar desire to reject the past in favour of the utmost presentness and the intoxication of the new - or, as he often characterised this avant-garde, 'art that boldly went where no art had gone before'.

He was also, as he often stated, a creature of the 1960s, and the excitement of that era was the only source of any tiny hints of nostalgia in his anecdotes (actually, a little also crept in when he spoke about his daughter or granddaughters). In virtually everything he did, he faced firmly towards the future, even to the extent of spending most of his life interested only in living composers and the openness of stories yet unfinished. So with this caveat recorded:

Toop: the achievements

Richard's primary motivation as a scholar was to understand composers, the creative process, and the nuts and bolts of how musical works were created. He established the history of early multi-serialism (or total serialism) in 1974 in 'Messiaen/Goeyvaerts, Fano/Stockhausen, Boulez' - now regarded as a classic article.1 His multiple publications on Stockhausen were landmarks. His analysis (proceeding from the sketches) of Brian Ferneyhough's Lemma-Icon-Epigram was described, by Paul Griffiths, as 'belong[ing] with Ligeti's of Structures 1a as a modern classic of the genre'.2 He charted the work of composers who had been placed under the New Complexity banner (Finnissy, Dillon, Dench, Barrett) in 'Four Facets of the New Complexity'3 and was later incorrectly blamed for coining the term.

Richard was immensely proud of a fax from Ligeti, displayed on the wall of his office for some years, in which Ligeti said Richard's monograph really 'gets' him.4 Stockhausen and Ferneyhough both also credited Richard with rare insight into their work. Stockhausen invited Richard to lecture in his summer courses at Kürten from 2002 to 2008, and some of these analytical lectures were published in book form.5

Several weeks before he died, Richard gave me permission to upload pdfs of his articles to the academia.edu website. I'm learning that, if one counts the scripts of talks he regarded as ephemera, there are hundreds, and I'll be doing it slowly over several years. He has written on Liza Lim, Kagel, Kurtág, Robert HP Platz, Michael Smetanin, and others. He had been hoping to finish a book on Walter Zimmermann. His work is as wide as it is deep. Many of his liner notes have the quality of original scholarship.

I will take this trouble because Richard's work is not only important to other musicologists like myself, but because - and I think this was what he was most proud of - it has concretely influenced composers. Many composers I've met express awe and envy on learning I studied with Richard. They read his articles in order to understand what Stockhausen and Ferneyhough were doing, and how they were doing it.

Toop: influence on Australian music, and polemics

There is no doubt in my mind that Richard has played a major part in the history of musical modernism in Australia. For a start, he taught composition to a group in Sydney who came to prominence in the 1980s: Michael Smetanin, Elena Kats-Chernin, Gerard Brophy and Riccardo Formosa, and later to other significant figures such as Damien Ricketson and Matthew Shlomowitz. He also influenced generations of performers and teachers through his music history lectures at Sydney Conservatorium. As Peter McCallum noted recently, Richard was proud to have educated them to the point they 'could distinguish between Xenakis, Stockhausen and Ferneyhough purely on the basis of the sound'.6

Richard's presence here, his teaching, his public talks, his lengthy, boozy lunches with many of us: he made sense of modernism's aesthetic and technical bases, he challenged us to find our own relationship to it, he helped uncover its beauties, and through his many anecdotes he allowed us to imaginatively entertain the possibility of hanging out with Kagel and Stockhausen. He brought the critical attitudes of Darmstadt and Donaueschingen to Sydney as we saw how he approached premieres and endlessly discussed aesthetics. Michael Smetanin has had multiple premieres and commissions in the Netherlands. Damien took his ensemble to Warsaw Autumn. Richard made modernism's (Euro-centric) internationalism part of our lives. ELISION flourished.

There will be, however, those who remember Richard's presence less fondly. Richard enjoyed polemicising. I have seen major composers (for whom he advocated passionately) tremble when approaching him after a premiere. Richard had a masculinist and oedipal view of art: toughen up, I can imagine him saying. He told me that his critical salvos were a sign of respect, and it was when he didn't bother to speak with you or critique you that he was really uninterested. 'Australians cannot cope with discourse', he would say.

As an incorrigible relativist and child of postmodernism, I can't take this attitude myself. But I insist on this as we remember him: he was much more stylistically open-minded than his reputation suggested (he loved Vivier's music!) and he wanted nothing more nor less than to be challenged. He was enormously open-minded and completely lacked fear when it came to being challenged or having his mind changed. In fact, that's what interested him, he craved it. A committed modernist perhaps, but one completely against orthodoxies of any sort. The future was open, as he saw it, and so was he.

I have stories that demonstrate this. The reason he supported me professionally was because I was apparently rare, amongst those who had taught with him, in that I wanted to change what he'd been doing, and I frequently argued with him. One year, we taught music history with someone who had been at UCLA (in Richard's view, the home of highly suspect postmodern musicology, 'McClary-land' he called it). He sought this situation out as he was interested to encounter what these ideas might have to offer in a teaching context and to be challenged himself. Above all, he was hoping he would hear something interesting.

It's also worth noting how entertaining Richard's own critical salvos were. In the 1980s, when bemoaning the insufficient amount of Australian music on the ABC, he called the classical station 'muzak for a North Shore retirement village'. He was fairly sanguine and unsurprised that this marked the point at which he ceased being asked to make radio programs.

Toop: vignettes from his personal history

Born on 1 August 1945, Richard was nearly not born at all as the house beside that in which his father and pregnant mother were sleeping was destroyed in the Blitz. He had a southern English childhood, and if the privations of postwar England touched him they seem to have been mostly forgotten in favour of the excitement at being taken to London and introduced to museums and culture by his two aunts.

At a regional grammar school he won the music prize in 1962 and asked for the score of The Rite of Spring, which was presented by the future Prime Minister Edward Heath, only recently nicknamed by Private Eye magazine 'Grocer Heath'". Richard appended 'grocer fugue' to this, for a reason that no doubt made sense when he told me about it, a few years ago, over an indeterminate number of glasses of wine.

Richard's own words best describe his engagement with new music in this period:

'...imagine, if you will, a tubby teenage Toop in 1962; he's sixteen. He's already utterly intrigued by the 'New Music' phenomenon, but he's still very much a beginner, trying to work out what's going on. Where does he get to hear it? Almost exclusively, on the radio. The BBC Third Programme has a weekly Thursday Invitation Concert which has consistently fascinating repertoire, including mediaeval and Renaissance music, hard-line classical chamber music, and every now and then some radical contemporary music. But the main source is the Continent. He soon discovers that the most promising time for 'new music' broadcasts is late in the evening, when he's lying in bed, trying to find programmes using the rather random efforts required by an old crystal set. So one evening in late May, he's prodding away, and out of the blue, he happens on a rather crackly version of… a 25-minute block from MOMENTE… on West German Radio. Was that an Epiphanic Moment for me? I'm not sure I really believe in such fancy terms, but be that as it may, it came pretty close. I remember the sheer impact of the music; I remember being utterly astonished.7

In the early 1960s he also had live contact with composers and their new scores: at the Dartington Summer School in 1961 he heard Berio, Nono and Maderna, and the following year, Lutoslawski. At this point, he was composing, and his final piece at school was partly determinate, partly indeterminate, scored for spatially separated instrumental groups. Soon after, he taught himself German, primarily to read Die Reihe.

In the late 1960s Richard became active as a new music pianist around London; repertoire included Cage's Concert for Piano and Orchestra and several of La Monte Young's Composition 1960 pieces. Most notable, perhaps, was his performance in October 1967 of Eric Satie's Vexations, lasting about twenty-four hours at the Arts Lab, Drury Lane; it seems to have been the first documented solo performance of the work.8 The photograph at the piano with the mug (see photo on the left) was taken during this.

Contact with Stockhausen began in 1969, and from 1972-1974 he was

Stockhausen's teaching assistant at the Staatliche

Musikhochschule in Cologne; lessons mostly took place in

Richard's apartment and, after several hours' analysis, Richard's

wife Carol served refreshments and baby Samantha was allowed, as

Richard put it, to 'terrorise' the students. These included

Claude Vivier, Walter Zimmermann, Moya

Henderson, and Kevin Volans. I asked Walter, years later, if

Richard had been 'like this' - i.e. musically encyclopaedic and

erudite - at the age of 28. 'Oh yes!', he said.

Relations with Stockhausen deteriorated in 1974 and, back in

London looking for employment, Richard heard from Roger Woodward

about a lectureship at the (then) N.S.W. State Conservatorium of

Music. So began a 35-year association and the advent of the

Australian part of Richard's life.

Australians, conscious of their peripheral position in relation to the centres of new music Richard wrote about, often asked him, 'What are you doing here?' He usually noted that he came for the job but also that he liked it here. For one thing, it provided an opportunity for a productively distanced view of those centres of new music. Secondly, he said that, after disembarking on his first flight into Sydney, the taxi took him through Kings Cross, and, on noting several Italian and Greek restaurants, he thought, 'This will do, this will do.' The wine he subsequently bought confirmed the impression.

Closing

What Richard sought in life and art was amazement, wonder, and, in the nineteenth-century sense, transcendence. I asked him recently if he thought Schoenberg's music really was the result of his analysis of the German classics and a self-conscious attempt to combine their qualities, and if this was what led to much of it being so difficult. He agreed but noted that this was what made it wonderful: the aesthetic, technical and emotional gymnastics whose effect was to thrill.

What a tremendous voice lost - American musicologist Rebecca Y. Kim

New music needs strong advocacy and Richard was one of the strongest and best. He was passionate and persuasive about some of the most challenging repertoire that has ever been written: Richard made it all make sense - Matthew Hindson

Further links

'Vale Richard Toop' - an article and tributes on the Sydney Conservatorium of Music website

'Richard Toop has died' - an article in the Limelight (20 June 2017)

"Vale Richard Toop - a force in our musical culture' - an article on the RMIT Gallery website

Footnotes

1. Richard Toop, 'Messiaen/Goeyvaerts, Fano/Stockhausen, Boulez', Perspectives of New Music 13, no.1 (1974): 141-69.

2. Paul Griffiths, Modern Music and After (Oxford, 1995), 299.

3. Richard Toop, "Four Facets of the New Complexity" Contact no.32 (1988): 4-50.

4. Richard Toop, György Ligeti (London, 1999).

5. Richard Toop, Six Lectures from the Stockhausen Courses Kürten 2002 (Kürten, 2005).

6. http://music.sydney.edu.au/vale-richard-toop/

7. Richard Toop "Climbing a Musical Everest: Unravelling the sketches for Stockhausen's MOMENTE", Paper presented at the Sydney Conservatorium Musicology Colloquium Series, March 2014.

8. http://www.gavinbryars.com/work/writing/occasional-writings/vexations-and-its-performers#_edn8

© Australian Music Centre (2017) — Permission must be obtained from the AMC if you wish to reproduce this article either online or in print.

Subjects discussed by this article:

Rachel Campbell teaches music history and musicology at the Sydney Conservatorium. She is currently writing a book about the beginnings of Peter Sculthorpe’s career and the history of Australian musical nationalism. She was an enthusiastic discussion partner and friend of Richard Toop’s for over twenty years.

Comments

Be the first to share add your thoughts and opinions in response to this article.

You must login to post a comment.