8 June 2011

Insight: Symphony by Gordon Kerry

Gordon Kerry continues our new 'Insight' article series, in which the AMC's represented artists take a close look at some aspect of their own work. Kerry's Symphony will be broadcast on ABC Classic FM on Saturday 11 June at 1 pm. (Read also: Erik Griswold and Vanessa Tomlinson's 'Insight' article about Clocked Out's collaborative project Wake Up!).

In 1994 the Sydney Symphony Orchestra performed my first major orchestral piece, harvesting the solstice thunders, with Mark Elder conducting. It was well received, but Laurie Strachan, then The Australian's Sydney music critic, complained that composers, like police officers, now seemed young enough to be his children. I wasn't that young, really, but working with as experienced a conductor as Mark was amazing for a relative neophyte. In the hours we spent before the rehearsal period, Mark showed a mind-boggling attention to detail: how, for instance, adding an up-bow to the second semiquaver of this group will make for a more convincing forte 12 bars later.

The lesson, duly learned, sounds like a statement of the bleeding obvious: that orchestral players like unambiguous instructions in the score as much as they do a clear and precise downbeat from the conductor, and they appreciate a composer's efforts to understand the technical aspects of their playing. I have tried to apply those lessons, and some years ago it was heartening to receive one of the greatest compliments I have had from an SSO musician: while clearing up a copyist's error that had rendered a particular figure on the instrument unplayable, she remarked 'I didn't think you'd do anything that stupid'.

That bespeaks a certain familiarity, and since 1994 the SSO has indeed commissioned several of my orchestral works and performed many more. Those commissioned include Such Sweet Thunder, my response to Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, which was conducted by Markus Stenz, a Clarinet Concerto for Frank Celata, also conducted by Mark Elder, and Viol Bodies for violin, viola, cello and double bass for the Sydney Symphony String Fellowship program. The Orchestra has performed my Viola Concerto, with Esther van Stralen and conductor George Pehlavanian, Splenderà, under Jahja Ling, and gave the first Australian performance of Upon Empty Air with Federico Longo conducting. So when I was fortunate enough to receive the Established Composer Fellowship from the Ian Potter Foundation in 2009, and knowing that, were I spared, I would turn 50 in 2011, it seemed an ideal opportunity to write a major work for an orchestra I know very well.

Inevitably, I suppose, I was drawn to reflect on my previous work, and my numerous fans will no doubt notice certain similarities of detail to earlier pieces: the recurrent structural gesture, if not the actual material, of interrupting a climactic moment with a '...many of my orchestral pieces to date have been, effectively, symphonic poems, taking their initial impetus from a particular poetic or visual image...' suddenly serene string passage harks back to Clouds and Trumpets, an overture I wrote for Oleg Caetani and the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra on the occasion of the orchestra's centenary; I'm fond of using the horn section in unison against busy textures, I love the golden late-Wagnerian thread of oboe, trumpet and a line of strings in unison, I love the sudden icy clarity of natural harmonics on the strings: these kinds of sounds can be found in other works. Like any artist, I have to be self-critical enough to know the difference between a stylistic gesture and a mannerism, but felt that the Symphony would inevitably be a kind of summa. It would, and I hope does, contain new elements - particularly in the structure of the harmony - but also some which may have appeared as rhetorical devices in 'programmatic' works, now in the service of abstract architecture.

I say 'abstract' because, as a glance at the titles I've mentioned will show, many of my orchestral pieces to date have been, effectively, symphonic poems, taking their initial impetus from a particular poetic or visual image. This, of course, has been a popular gambit for centuries, allowing composers to give pieces an extrinsic narrative structure rather than following the dictates of some real or imagined textbook form, and offering audiences a hook that might make unfamiliar musical language more immediately intelligible.

My formally abstract works to date had been a set of Variations for the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra under Markus Stenz (the standard-issue contemporary Australian 10-12 minute curtain-raiser) and the concertos for viola and clarinet. Other large-scale pieces have included Kindled Skies, a song cycle for Merlyn Quaife and Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra under Howard Shelley, and choral-orchestral pieces like For those in Peril on the Sea, for Gondwana Voices and the West Australian Symphony Orchestra under Matthias Bamert. There, clearly, text to some extent imposes a form, and there is, similarly, an extent to which writing a concerto invites one to use certain structural features that in turn affect the overall design of the work, the most obvious being the exploration of the possible relationships between solo and tutti, between the individual voice and the mass.

In seeking to write a symphony, then, I was hoping to find a way

to create a large-scale structure that created and sustained its

own internal drama and logic through the manipulation and

development of thematic material, and the use of contrasts of

mood and colour, texture and speed. And along the way provide a

showcase for the SSO's disciplined ensemble playing and, in solo

passages, its many fabulous principals.

But, I hear you say, don't all symphonies, and many other pieces

besides, do just those things? Isn't that a bit retro? Do we

really need another one? To which I would answer 'yes', 'no' and

'why not?' Naturally, to call a piece a symphony is to nail a

certain set of colours to the mast, to aver that - while making

no claims for the quality of my own work - the genre is

extensible and flexible enough to admit an endless variety of

expressions. There is, as they say, 'chess' and a 'game of

chess'.

The term 'heritage arts' has recently appeared in what's laughingly referred to as our cultural debate. It's a cant term for, among other things, classical music, opera and ballet. 'The term "heritage arts" has recently appeared in what's laughingly referred to as our cultural debate.' The unspoken, and implicitly pejorative, adjective is 'western'; non-western traditions built on the heritage of centuries are simply world music, as if Mozart came from Mars. Western heritage music is 'elitist' (bad unless you're Ian Thorpe) and 'expensive' (unlike a ticket to, say, U2), and one occasionally hears fatuities about the carbon footprints of performing arts companies.

While there are, regrettably, numerous examples of misguided marketing that play on notions of exclusivity and prestige, there is a great deal of wisdom in Alex Ross's formulation that classical music 'might not be for everybody, but it's for anybody'. That was certainly my experience growing up in suburban Melbourne, where fellow AMEB candidates and youth orchestra members came from a huge variety of, shall we say, socio-economic backgrounds - a genuine meritocracy. And it's certainly been my experience in my adult professional life working with student and amateur musicians, especially, in the latter case, in regional Victoria and New South Wales.

A companion piece to my Symphony, in that it, too, was composed with support from the Potter Foundation, was the overture In iubilo. It was written for the Bendigo Symphony Orchestra, a band made up of teenagers and senior citizens (and many in between), of professionals and tradies who love playing heritage music and who were delighted to have a work composed to their particular strengths. It was premiered in April, and will be performed again on 26 June in Bendigo.

The relationship between heritage, or tradition, and innovation was nicely described by Stravinsky, who knew a thing or two about both, and his words speak to the question of whether it is merely retro to compose a work like a symphony:

'Tradition is entirely different from habit, even from an excellent habit, since habit is by definition an unconscious acquisition and tends to become mechanical, whereas tradition results from a conscious and deliberate acceptance. A real tradition is not the relic of a past that is irretrievably gone; it is a living force that animates the present… Far from implying the repetition of what has been, tradition presupposes the reality of what endures. It appears as an heirloom, a heritage that one receives on condition of making it bear fruit before passing it on to one's descendants.'

Sadly, not long before the premiere of my Symphony, Benjamin Northey had, with very good reason, to withdraw from conducting the concert. The SSO's Associate Conductor, Nicholas Carter, stepped into the breach, learning the Bartók Concerto for Orchestra, Grainger's In a Nutshell Suite and my Symphony in three days. I had seen Nick conduct before, both orchestral music and opera, and knew that with his technique and calm authority I had nothing to worry about. But it was a big and complex program, and I suspect many a conductor would have baulked, or panicked, and insisted on changing the program to include works more familiar to him or her. Nick, perhaps, didn't have time to think about it, which is probably just as well, and in the event gave excellent performances of all three works to the always open-eared, predominantly young Meet the Music audiences. Who were very kind about my work. In all of this I found myself sympathising with Laurie Strachan's lament back in 1994: while Ben Northey is impossibly fresh-faced for a conductor, Nick Carter doesn't just look, but, at the age of 25, is young enough to be my son. Actually, though, it gives me great joy to hand my work over to someone a generation younger, in that it proves that our heritage is, in Stravinsky's formulation, bearing fruit, and I hope that my Symphony is a worthy contribution to that tradition.

Further links

Gordon

Kerry (AMC profile)

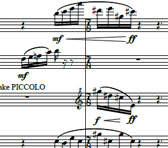

Gordon Kerry: Symphony - score sample and all details in the

AMC online catalogue

© Australian Music Centre (2011) — Permission must be obtained from the AMC if you wish to reproduce this article either online or in print.

Subjects discussed by this article:

New works of Gordon Kerry’s, premiering in 2011, include works for the Bendigo Symphony Orchestra, St Francis’ Church, Melbourne, the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, a song cycle to poetry of John Kinsella for Merlyn Quaife and Andrea Katz, and Captain Flinders’ Musick, for flautist Alison Mitchell and the Scottish Chamber Orchestra. The orchestral works were all written as part of the Ian Potter Established Composer Fellowship. Kerry is currently completing a new work with Louis Nowra for Opera Victoria’s 2012 season. In 2009 Kerry’s book, New Classical Music: Composing Australia was published by UNSW Press. He studied at the University of Melbourne with Barry Conyngham and lives in north-eastern Victoria.

Comments

Add your thoughts to other users' discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Bravo again

by Andrew Ford on 8 June, 2011, 3:24pm

Bloody good article, Gordon. I'd forgotten the Alex Ross quote: how true! And the Stravinsky quote: where's it from? Boulez says that tradition is merely a collection of mannerisms, but I think Stravinsky is far closer to the mark. As for first symphonies at 50, you know you've joined a rather exclusive club that has for members Elgar, Ross Edwards and me.

Thanks

by Gordon Kerry on 8 June, 2011, 3:56pm

Kind of you to say so, Andy, and I'm proud to join such a club if it will have me as a member! The Stravinsky is from the Poetics of Music in the Form of Six Lessons and I agree, unsurprisingly, that it's nearer the mark than Boulez's view. (Though remind me when he said that - B On Music Today?')

Club membership

by Andrew Ford on 8 June, 2011, 4:55pm

Well, I'll propose you and I don't imagine Ross will object. Elgar hasn't been financial for some time. I gather those Stravinsky lectures weren't really written by him, but he spoke the words and that's what counts. Keating, after all, didn't write the Redfern Park speech. The Boulez line is from a recent interview. Guardian? Possibly even Gramophone, though if the latter I may have him confused with Katherine Jenkins.