18 December 2009

Paul Jarman's Known Unto God and Pemulwuy

Image: Paul Jarman

Image: Paul Jarman 'Some pieces require weeks of strategy and planning. Others just happen', writes composer Paul Jarman. Here, he describes the composition processes of two of his choral works, Known Unto God and Pemulwuy.

Known Unto God

Music and lyrics by Paul Jarman

SSATB choir with bass trombone, cornet, tom toms and tenor

drum.

With special thanks to Artistic Director Kim Sutherland, the

choir and parents for taking part in the initial stages of

research for this piece.

Waiting, watching, hoping, praying,

Some day you're coming home.

Brother for brother, mate for mate,

No one thought it would come to this.

Someone's father, someone's son,

The dead lay side by side.

Cry for mother, cry in vain,

She will never hear your plea.

Someone's husband, broken heart,

Distant dreams, dying screams.

A generation disappears.

Daddy, please come home.

Fields of glory shroud wasted lives,

Where Christian fought Christian and few survived.

Above their remains carved into a cross,

The same three words, 'Known unto God'.

'Known unto God' but fighting for King.

'Known unto God' and dying in vain.

'Known unto God' who art in Heaven.

'Known unto God' and blown straight to hell.

We will never know who they were,

We'll never really know.

We will never know who they were.

We can only try to care.

In 2006 the Hunter Singers, directed by Kim Sutherland, commissioned me to write a choral work about the experience of Australians on the Western Front during World War I. In April 2007, after an Australian premiere, the piece would be performed in England and significant sites throughout the Somme in Belgium and France, with a special performance in the Last Post Ceremony at the Menin Gate, Ypres. This was the first time an Australian piece about the Western Front was performed in this ceremony. It was also performed at the Place de la Madeleine in Paris. I was fortunate to be invited to travel with the choir. It was a very powerful time for everyone.

The title of this new work, Known unto God, refers to the insignia etched into the headstones placed above the bodies of the fallen who were so terribly wounded that they were no longer recognisable. As there are tens of thousands of these across France and Belgium, I felt that this was a powerful message in itself. My research was extensive and included the work of Les Carlyon, the poetry of Siegfried Sassoon, E.P.F Lynch's war diary Somme Mud, and many other reference books, poems and songs. I also collected hundreds of quotes written during the war and incorporated 40 of them (one for each chorister) into the piece as a way of representing the opinion of the time: quotes from soldiers, mothers of soldiers, generals and officers, politicians, presidents, poets, and philosophers. Using both spoken and sung quotes, firstly in order and then improvised randomly into thick textures, I hoped to represent the slide into total chaos, the massive loss of life, the sheer hopelessness of it all, and the plea for an end to war itself. The ironic, final quote by President Woodrow Wilson is sung in unison: 'This is a war to end all wars'.

A writing team comprising ten members of Hunter Singers worked with me for two days at the outset of the project. To select the team, each student was interviewed about their background reading and their own family histories in relation to the Great War. They also visited the Australian War Memorial in Canberra to continue their research, and gained access to family archives. The Last Post Ceremony at the War Memorial at the end of the day was very moving and helped to remind the students of the great suffering and loss of life. The students came away with a greater depth of understanding about the impact of the war on the lives of Australians.

For me, the challenge of writing about an event of such magnitude, an event which impacted on so many millions of lives, was how to represent it accurately and emotionally. Do you tell the complete history, or one story? Do you focus on sounds and colour, rather than story? I felt that it had to be a combination and decided that the best way to connect all story was through family. With this as a guide, the piece could find an emotional DNA, a link between generations, and a way to tell the story, not just from the battlefields but from the perspective of humanity itself.

One story which resonated for the group was that of Annabel's (a year 10 student from Lambton High School) great grandmother, Hannah, who is 94 and suffering from Alzheimer's. Hannah remembers her childhood and how, when she was just a little girl of six, a stranger approached her outside her house and said: 'You must be Hannah; I'm your father'.

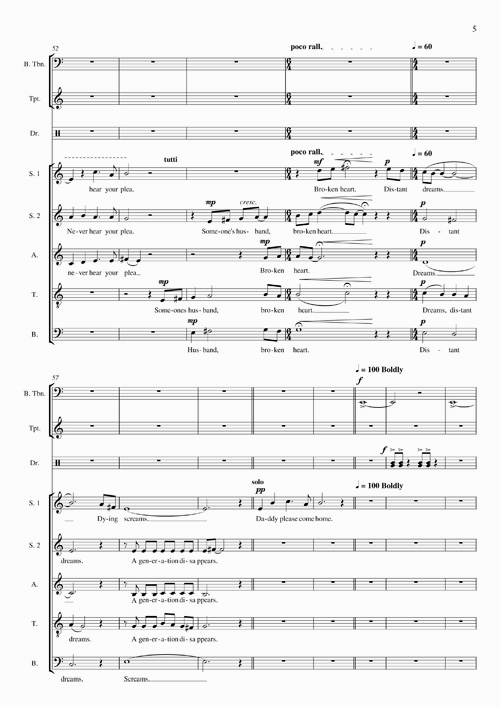

We began the piece working on a way to capture the sense of longing that Hannah must have felt for her absent father. ('Daddy, please come home', bar 60).

Music example 1 (click to enlarge): Known Unto God, bars 52-64.

Using the image of this little girl, the piece interweaves the concept of father, brother, wife and daughter, mother, son and husband into the larger story of the war, through the battlefields and back home, to the horrible aftermath. The final section of the piece is set in the present.

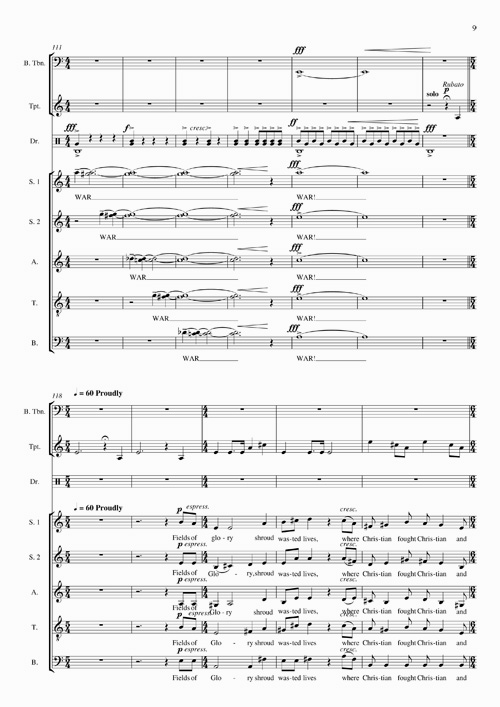

The piece could be divided into four main sections, although some themes appear within the diorama several times.

1. The little girl waiting for daddy to come home, as metaphor

for a lost generation. Bars 1-12, 60-62

2. The war, incorporating 29 spoken and sung quotes from

soldiers, poets and writers of the time. Bars 13-117

3. The consequences of war ('Fields of glory shroud wasted

lives'). Bars 118-140

4. A final prayer and reconciliation with the past. ('We can only

try to care'). Bars 141-153

The accompaniment comprises cornet (playing The Last Post), bass trombone, tom toms and tenor drum. Two trombones can be used on opposing sides of the stage for a stronger effect. The piece concludes with the last line of Waltzing Matilda, sung as a prayer for the fallen. Initially I had not thought of including The Last Post. Towards the end of the writing I felt, however, that there was a problem of spacing between the end of the war section and the start of the reflection. To me, it felt too sudden, and I needed a way to suggest that time had passed. I imagined the choir singing in the cemeteries and realised the obvious. It was so right for me, visually, that I immediately placed The Last Post over the top of the existing music, and it worked perfectly. I guess it was always meant to be. One of the choristers, Eleanor, performed it beautifully and under a lot of pressure: she, too, had relatives buried in Flanders, and it was never going to be easy to play that piece.

My addition of Waltzing Matilda also came very late in the writing. I included it to enhance a sense of place and country, and musically it fits very well as a counter-melody to The Last Post.

The addition of the quote section was part of the initial planning for the piece, but the rest of the work was written spontaneously, without a map of the structure. I let it evolve scene by scene. I had no concept for the last two post-war sections until I had completely written the rest of the piece. Only once I had reached the end of the war itself did I feel comfortable with the process of reflection.

As the choir were directly involved in the creation of the work, I knew that standing in the fields of Flanders singing it would be extremely powerful, and at times difficult, especially for those with relatives buried there. This inspired the section from bar 118 'Fields of glory shroud wasted lives', where the story has shifted into the present day. Hopefully, then, any generation can sing this piece with the same impact in the future.

Music example 2 (click to enlarge): Known Unto God, bars 111-122.

The piece lasts for approximately 12 minutes and is performed as a confronting theatrical work. As The Last Post and Waltzing Matilda combine, the choir sings 'We will never know who they were, we'll never really know. We will never know who they were. We can only try to care'.

Will we ever learn?

Pemulwuy

Music and lyrics by Paul Jarman

Eora Language source, Eric Willmot's Pemulwuy

Dedicated to Eric Willmot and the Eora Nation

Duration: 3.30

Woyan Camya, Yanada rising.

Where the night winds howl the crow is flying.

When the moon appears hear the raven call.

Where smoke is rising the crow is waiting.

When fires burn hear the raven cry.

Where the Bidjigal roam the crow is guarding.

When the spirits wail hear the raven call.

Where the clans unite the crow is leading.

When Eora charge hear the raven cry.

Pemulwuy, Pemulwuy!

Where the rum corps brawl the crow is scathing.

When the convicts scream hear the raven call.

Where farms are torched the crow is blazing.

When the settlers flee hear the raven cry.

Woyan Camya!

Where the enemy strikes the crow is immortal.

When the muskets roar hear the raven call.

Where the military fall the crow is rising.

When the war unfolds hear the raven cry.

They have come to take this land.

Something we will never understand.

Fighting for it seems so wrong.

We don't own the land, we just belong.

This is what we've known since the dreamtime.

We have the right to believe.

Eora, Darug, Tharawal, don't ever give up hope.

Woyan Camya.

Pemulwuy, Pemulwuy.

Hear the raven cry!

In 2006, I was commissioned to compose a treble choral piece for Woden Valley Youth Choir, directed by Alpha Gregory. After a premiere in Canberra it was to be performed on their next international tour to Europe. I had just read Eric Willmot's stirring book Pemulwuy, and it immediately felt right to honour Australia's first freedom fighter.

Pemulwuy was born around 1756 somewhere near where Homebush Bay is now. He belongs to the Bidjigal Clan of the Eora nation. The city of Sydney is built upon his land. The initial creation of this city took place during the last fourteen years of Pemulwuy's life. 'The legend of Pemulwuy is part of the belief system and oral history of the Aboriginal people of east coast Australia. It is also part of the history of all modern Australians', writes Eric Willmot.

Pemulwuy means 'man of the earth'. He was known as the Rainbow Warrior, and his totem was the crow. From 1790 to his death in 1802, Pemulwuy led the Eora people in a major response to the British invasion of Australia. The Aboriginal resistance is said to have been broken in 1805 when Pemulwuy's son Tedbury was captured and became the first Australian prisoner of war. This resistance, and indeed Pemulwuy's very existence, was hardly mentioned in records made at the time, possibly a way for both the Governor and military officers to avoid embarrassment or disciplinary action, due to various failed campaigns. To this day, little is said of Pemulwuy in Australian history books, although some advancement has been made in recent years, thanks to academics, artists and writers both Indigenous and non-Indigenous. There is a suburb near Prospect called Pemulwuy.

It is likely that Irish convicts and possibly an African American slave fought alongside Pemulwuy. Only two years after Pemulwuy's death, the Irish revolted against the British, resulting in the Battle of Vinegar Hill, which interestingly has also been marginalised in Australian history - strange, seeing that it was the first European conflict on Australian soil. According to Wilmot, 'It was apparently not in the interests of a crookedly intent or racist establishment to promote such parts of the Australian story'. Some documents, written by Governor Phillip and Sir Joseph Banks, do mention Pemulwuy as being a 'terrible pest to the colony', although it is possible that Phillip resigned from his post partly due to the struggle against Pemulwuy.

Pemulwuy was said to be invincible against the British weapons. Legend states that, on one occasion, he was shot seven times in the head by musket fire and was locked in a cell to die during the night. The next morning, the guards unlocked the iron door, and Pemulwuy had disappeared. A crow sat on the bars above the cell. Pemulwuy watched the destruction of the Sydney Aborigines due to small pox and other diseases. He was ambushed and shot dead in 1802. His head was sent to England and it has never been returned.

When I wrote this piece, I was fuelled by Eric Willmot's book and naturally disappointed in the history I was taught in school, growing up in the 1970s Australia. We were never told about Pemulwuy or even the Stolen Generations. I had no idea who he was until an Aboriginal artist/activist friend of mine, Adam Hill, alerted me. For me, writing Pemulwuy was a chance to celebrate a great Australian and to do something to make up for the missed opportunities in my education. Of course I also knew that the piece would be premiered right near Parliament House in Canberra.

Some pieces require weeks of strategy and planning. Others just happen. With Pemulwuy, it was the latter. I remember thinking about the image of a crow flying in front of a full moon, the wind howling through the gum trees, and that sense of ancient belonging. I decided to open the piece with Bidjigal words describing the crow and the full moon rising (Woyan Camya - the crow is coming; Yanada - moon). This symbolised Pemulwuy bringing his people together and launching a united attack.

Music example 3 (click to enlarge): Pemulwuy, bars 1-9

I wrote most of the lyric in the moment, while playing the driving piano part in the introduction. To me, it felt like a film score or a dance piece. I imagined Pemulwuy's lightness of feet, his speed and agility, his strength and conviction, and his warrior status.

The first half of the piece is a celebration of Pemulwuy and a retelling of some histories, including the burning of settler farms, fights against the Rum Corp and the unification of Aboriginal clans. The second half of the piece is more political. I wrote this as a beacon of awareness and reconciliation, for now and for the future, and looked at the history through the eyes of an Aboriginal Australian: 'They have come to take this land, something we will never understand. Fighting for it seems so wrong, we don't own the land, we just belong'.

In Pemulwuy, I push the choir and audience to the edge. I want extremities in dynamic range, passion and conviction within the lyric, and an understanding of the story. I have always asked choirs to pay extremely close attention to diction with this piece and analyse every word. In particular, the word 'raven' which is very strong and heard throughout the piece. I also like particular attention to tight cut-offs rather than sustained sounds dying out. It is a fierce interchange between the piano and the choir that I am after.

With this approach to clarity, dynamic and energy, the piece should lift off the stage and the audience should feel as though the crow or the dancer is among them in the dark. I have also workshopped choirs in an understanding of sound movement to enhance the rises and falls of the piece. It should feel like a score to a dance work.

I have seen the work done very well by choirs across Australia. The Birralee Blokes from Brisbane won ABC Choir of the Year in 2006 performing this piece, and SING NSW toured it with great success to Canada in 2007. The Woden Valley Choir recently performed it at their 40th anniversary concert.

The string arrangement and new choral parts were commissioned by the Three Choirs festival in 2008 under the direction of James Allington from Barker College, and the SSATTB arrangement was commissioned by the Canberra Youth Choir. I have also written the piece for TTBB male choir (see: Robert Braham's Journal article).

Thank you to all the choirs who perform Pemulwuy.

Quotes used in Known Unto God

We were marooned in a frozen desert. There was not a sign of life on the horizon and a thousand signs of death. (Wilfred Owen 1917)

When we started firing we just had to load and reload. They went down in their hundreds. You didn't have to aim. We just fired into them. (German soldier 1915)

Patriots always talk of dying for their country, and never killing for their country. (Bertrand Russell)

We had to remove the piles of enemy bodies from before our trenches, so as to get a clear filed of fire against new waves of assault. (Paul von Hindenburg 1917)

The cries of the wounded had much diminished now, and as we staggered down the road, the reason was only too apparent, for the water was right over the tops of the shell-holes. (Captain Edward Vaughan 1917)

The dead were stretched out on one side, one on top of each other six feet high. I can never describe that faint sickening, horrible smell. (Captain Leeham 1916)

No-man's land under snow is like the face of the moon: chaotic, crater ridden, uninhabitable, awful, the abode of madness. (Wilfred Owen 1917)

Independent thinking is not encouraged in a professional army. It is a form of mutiny. Obedience is the supreme virtue. (Lloyd George, British prime minister)

To fight, you must be brutal and ruthless, and the spirit of ruthless brutality will enter into the very fibre of our national life. (President Woodrow Wilson)

We were not making war against Germany, we were being ordered about in the King's war with Germany. (HG Wells 1914)

The safest thing to be said is that nobody knew how much a decoration was worth except the man who received it. (Sassoon)

Yesterday I visited the battlefield of last year. It was if the souls of the dead soldiers had come to haunt the spot where so many fell. (British Officer 1919)

If my own son can best serve England at this juncture by giving his life for her, I would not lift one finger to bring him home. (Mrs Berridge 1914)

We're telling lies; we know we're telling lies; we don't tell the public the truth, that we're losing more officers than the Germans. (Rothermere, journalist)

Only the dead have seen the end of war. (Santayana)

So marched into captivity all that was left of the 2nd company of the 165th Infanterie regiment: two officers and twelve men. (Gefreiter Fritz Heinemann 1916)

The brutality and inhumanity of war stood in great contrast to what I had heard and read about as a youth. (Spengler 1916)

There were many words that you could not stand to hear and finally only the names and places had dignity. (Ernest Hemingway)

His bones are mingled with the filth which they scatter to the four winds. (Gerhard Gutler)

Our hands are earth, our bodies clay and our eyes pools of rain. (Erich Remarque)

Our minds were so numbed that we no longer had any scruples about the whole thing. (Otto Hahn)

Anyone who says he enjoys this kind of thing is either a liar or a madman. (Captain Harry Yoxall)

This war is really the greatest insanity in which white races have ever been engaged. (German Admiral von Tirpitz 1914)

This is the end and beginning of an age. (HG Wells 1916)

Two armies that fight each other is like one large army that commits suicide. (Henri Barbusse 1915)

Abstract words such as glory, honour, courage or hallow were obscene. (Ernest Hemingway 1929)

In wartime the word patriotism means suppression of truth. (Siegfried Sassoon)

I believe that the war is being deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it. (Siegfried Sassoon 1917)

Men go to their deaths with curses on their lips and religion is never mentioned or thought of. (Private J Bowles 1916)

This is a war to end all wars. (President Woodrow Wilson)

The composer would like to acknowledge Les Carlyon for his book The Great War and also E.P.F Lynch and Will Davies for the powerful war diary, Somme Mud. The poetry of Siegfried Sassoon has also been a source of inspiration for this piece. The composer also acknowledges the website Heritage of the Great War.

Further links

Paul Jarman's music is available through the composer -

A version of Pemulwuy for SAA, percussion and piano has

been published as part of the Young Voices

of Melbourne Choral Series, along with some other works by

Jarman.

'Grandage's Wheatbelt, Abbott's Bundle of Joy

and Jarman's Pemulwuy' - a Journal article

by Robert Braham

© Australian Music Centre (2009) — Permission must be obtained from the AMC if you wish to reproduce this article either online or in print.

Paul Jarman is a widely acclaimed Australian composer, performing artist, Musical Director and educator. Paul is best-known as a passionate storyteller, as both a lyricist and composer of choral music, and as a world music multi-instrumentalist. Paul has worked extensively throughout Australia, Europe, Asia, North America, the Middle East and the Pacific with theatre productions, dance ensembles, Aboriginal-Anglo Celtic performance groups, special events, choirs and orchestras, and as a member of Sirocco since 1996.

Comments

Be the first to share add your thoughts and opinions in response to this article.

You must login to post a comment.