18 September 2007

Post Impressions: A Travel Guide for Tragic Intellectuals

Extracts from Hollis Taylor's new book/DVD

Image: Hollis Taylor and Jon Rose at Woomera

Image: Hollis Taylor and Jon Rose at Woomera An American woman (Hollis Taylor) and an Australian man (Jon Rose) set out to explore and perform on the giant musical instruments covering the continent of Australia: fences. In pursuit of their instruments, including the Rabbit-Proof Fence and the 3300-mile-long Dingo Fence, the duo survive several boggings, a fly plague, a flea infestation, deadly snakes and crocodiles, heatstroke, floods, storms, bush fires, and their own ignorance.

They travel 25,000 miles, engaging with a flying priest, an auctioneer, an Aboriginal gum-leaf virtuoso, the first piano in Central Australia, a singing dingo, fence runners, and other colourful bush personalities.

Their travelogue, by turns bent and philosophical, includes a bonus DVD of 40 outback fence performances, 88 colour photos, and fence music and birdsong transcriptions.

[Hollis and Jon at Woomera, SA.]

Excerpts from Post Impressions: A Travel Guide for Tragic Intellectuals by Hollis Taylor

The morning tiptoes in, all pastel except parrots whose plumage shocks in the rich hues of satin evening gowns. This pageant is of little interest to Jon, who is well on his way to becoming a fence nerd. He is anticipating Yalata and our arrival at the Dingo Fence, about an hour away as near as he can tell.

It's the world's longest man-made structure, he rattles off, traversing 3,300 miles across three states, well more than twice as long as the Great Wall of China.

I've been slow to warm to it. This Fence doesn't figure on most maps, and when it does, it's a vague dotted line progressing in fits and starts as if the unsure hand of its cartographer had erased the displeasing bits, or as if some parts of it flow through prohibited areas under state censorship. It's downright un-American, this subtlety. Where are the T-shirts, the bragging billboards? Who will write its tourist text? If the Dingo Fence does not command a sign, a shop, or a TV screen, I won't believe a word of it.

As we roll over a grid, Jon shouts, Back up! Back up!

Something clicked in his brain: grid=fence. Yes, it's here, well before we expected it. We pull down a steep gravel embankment and get out for an inspection. Its six feet of wire mesh conclude with six inches of rabbit netting embedded in the ground. Warning signs hang from it: Keep Out, Permission Required, Danger: Poison (1080 poison is used along the Fence for lacing dingo baits). Jon never bothers obtaining permission. This will not even slow him down.

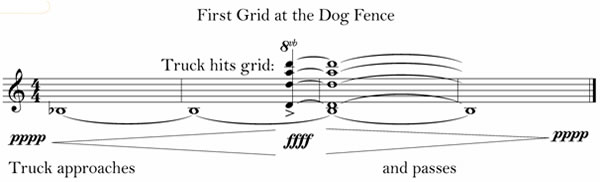

The Fence spans both sides of the highway, not so much interrupted by as continued by the unusual grid, a massive framework of widely spaced, narrow metal bars about 10 feet long. I can barely walk on it; clearly it's meant to stop something more agile and wily than cattle. When the heavy trucks roll over it, the grid rings out like a symphonic gong. Jon records every truck for 20 minutes and then performs a drum solo on the grid with sticks and brushes. Next, he plays the attached fence, which the grid amplifies as well. Farther down, we improvise a double bow solo on the dusty, barbed Fence proper.

___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

We can't depart without bowing Milparinka's Dead Sheep Fence (as we name it). The plus: a great-sounding fence, God's own instrument; the price: there's a dead sheep here, its head wedged between two main posts right where we're bowing. We seem to specialize in playing for the dead of late. The sheep's final resting fence begins to groan and moan, whine and complain with the prompting of our bows. A frenzied saxophone/percussion duo you'd think to hear the recording, the all-hell-breaks-loose pandemonium of a spirit that cannot find rest. The sheep's eyes must be long gone but the illusion of their presence is fixed; they stare into eternity.

[Jon bowing at the Dead Sheep Fence, Milparinka, NSW.]

___________________________________________________________________________

[A classic corrugated iron fence, Winton, QLD.]

___________________________________________________________________________

The Coober Pedy dawn chorus is a rooster, a pigeon, and a drunk. Jon promises and promises an easy day, no extra projects, only the Dog Fence. But we turn around after 20 seconds to re-examine a fence on a high hill—could it be an abandoned mine? We stop a few minutes later at an opal field to “just test” the perimeter fence. It’s slack. I’m off the hook, I assume. But slack + wind = aeolian harp. We record and film the fence; then, he records a vibrating Deep Mine Shafts sign. Vibrating is probably the wrong word; it’s a wind-crazed, shaking metal spirit.

Red sand and gravel everywhere, sun in my eyes, driving blind on a bad road—if you’re unsure of your age, go to a nightclub or rent a four-wheel-drive vehicle. At the Dog Fence, he suggests that she will pound a large rock on the fence post—not a musical technique taught or imagined when I was at school. Then Jon does a walkin’ the fence routine with a stick bouncing along the wire. With the contact microphones in place and my headphones on, it’s a crescendo-descrescendo any drummer would be proud of. Jon improvises on violin with the fence behind him, then turns to the camera and speaks:

The fence as a functional long-string instrument is a result of industrial mass production—something Stradivarius would have found hard to get his brain around. Despite the cultural Dark Ages that we now find ourselves in, new design for string instruments can still be found. This is a Vatilliotis tenor violin, made in Australia just three years ago. It sounds one octave lower than the standard model. Historically speaking, experimentation has always been a fundamental part of string instrument making. Within the Islamic tradition and its European offspring, there were rarely times when innovation wasn’t the modus operandi.

The creative musician in this country is always being told by those who run our culture that the great Australian public is not interested in new music—they only want to hear the tried and tested, the copy. This patronising attitude is one of the reasons why no identifiable genre such as bebop or reggae ever evolved in the modern state of Australia. Even Canada has its own fiddle tradition.

Where I’m standing now is right beside the Dingo, or Wild Dog, Fence. It’s arguably the longest man-made anything on our little planet. It stretches through three states, and as its name suggests, it was constructed and is regularly maintained to keep the Australian beef and sheep industry south of the fence dog free. Now one thing’s for sure: the guys who built this fence weren’t concerned with the theory and practice of music as they laboured away under a scorching sun. But we have to thank them, because they unwittingly designed and constructed the world’s longest string instrument.

[Dingo Fence, Coober Pedy, SA.]

___________________________________________________________________________

Unbelievably flat and uninteresting …Herbert Hoover is quoted as saying, not of his own personality but of the Kalgoorlie area of Western Australia. He could have been here, at the remains of the Woomera Detention Centre. Looking out, it's bleak: flat, barren, isolated, and grey. Looking in, the fence borders a concrete floor the size of two football fields. The show has pulled out. Small canvas bags resembling pillows full of sand or dirt or hate are scattered about.

Hell for refugees who finally reach the lucky country. On closer inspection, the pillows seem to have been placed in some kind of formation. Prayer mats? That’s it—a religious ceremony has taken place quite recently, and all the devotees have been snatched up into the Islamic equivalent of rapture just like that. No time to finish the prayer.

[Scattered prayer pillows at the Woomera Detention Centre, SA.]

Curious Aboriginal children flock to us as we design the where and how of our musical fence. Jon unpacks his bass bow.

He’s gonna use that stick to play the fence, says David.

You liar one, Kirin retorts.

The musical fence is three treated posts and several lengths of piano wire. The kids hang around the edges, just waiting to give the stretched wire a tug. Other than having to guard our instrument, it’s all going well—but then several women approach Jon with a concern.

You can’t play music with these. Them posts dead ones. We gotta bring ‘em back to life. We paint ‘em up.

Really? Yes, please.

Bernadette Tjingiling, Marita Sambono-Diyini and Christina Yambeing have never painted together before. Sharing a pie plate of yellow, red, green, blue, white, black, and magenta acrylics, they sit on the ground around a post and communally cover one at a time. The first has turtles, fish, snakes, and other animals climbing a pale blue post. The second features the bush yam with soft brushwork. The third is cram-full of bright flowers and dragonflies. It’s the time of year that dragonflies come out; they herald the beginning of the Dry, although they are late this year due to the weather.

There’s magic with ‘em, we’re told.

The three women work late into the night. The next day, after we perform on the fence, the kids can hardly wait to give it a good thrashing; then the painted posts get auctioned off along with the year’s best crop of paintings. Every available space on the vibrant posts celebrates some living thing.

© Australian Music Centre (2007) — Permission must be obtained from the AMC if you wish to reproduce this article either online or in print.

Subjects discussed by this article:

Hollis Taylor is a violinist and composer. Taylor's sound/video installation Great Fences of Australia, in collaboration with Jon Rose, has seen numerous international performances. Her full-length book Post Impressions: A Travel Guide for Tragic Intellectuals is based on her and Rose's 35,000 kilometre journey as cartographers making a sonic map of the great fences of Australia.

Comments

Be the first to share add your thoughts and opinions in response to this article.

You must login to post a comment.