28 July 2016

Insight: Improvising and composing for The NOISE

Image: Paul Cutlan

Image: Paul Cutlan Composer Paul Cutlan has a strong background in jazz and improvisation - in this Insight article he writes about employing improvisation in his recent composed works for The NOISE string quartet. 'Delegation of authorship and creative responsibility can give performers more of a sense of personal investment in a work', he writes, while 'composition in the traditional sense affords the luxury of reflection and revision, as well as large-scale design'.

> Read more 'Insight' articles by the AMC's Represented and Associate artists (Scoop.it).

Many of my pieces over the last five years reflect the growing tendency by composers to incorporate improvisation into through-composed music. Whereas jazz music mainly relies on repeating harmonic cycles as a bedrock for improvised solos, the concept of employing improvisation into notated music, which travels in a straight line from beginning to end, poses different challenges to both composer and performer. The composer has to consider how improvisation will affect or contribute to musical form and how best to integrate improvised elements into a set structure. Another issue is the task of the performer's familiarisation with the vocabulary necessary to make such improvisation relevant to the overall piece.

My path to composing works which employ improvisation has had a long gestation, starting with inspirational teachers and being fed by experiences both as a classical and a jazz musician. Currently I am a part-time composer, with composition complementing my activities as a predominantly jazz performer and improviser.

My introduction to jazz was via a high school teacher Chris Allen, who ran a stage band in which he actively encouraged students to take solos and improvise. This discovery of the thrill of spontaneous music-making and the self expression it afforded sowed deep seeds for the future. My HSC music teacher Philippa Moyes opened my ears and mind to composers of the 20th century, starting with composers like Stravinsky and Britten. Since then, my study and love of jazz and classical music have evolved in a way that has curiously kept them separate in my mind. Only in the last six to ten years I have found a way to integrate these passions through the combination of composition and improvisation.

For the last twenty years, my performance career has included participation in a number of original jazz and world music ensembles. Thanks to composer/band-leaders such as Llew and Mara Kiek, Sandy Evans, Tony Gorman, Andrew Robson, James Greening, Alister Spence and many others, I have become familiar with forms of composition which combine jazz improvisation with other styles and traditions. The pieces these musicians write serve as templates for a composition to unfold with the aid of improvisation and a shared knowledge of various performance practices. I remember being amazed at how sophisticated the form and arrangement of a 7-10 minute piece could be, only to discover it would often be based on a single page of notated music.

Another feature of these compositions is that their eventual realisation often depended heavily on collective workshopping within its intended ensemble. Bands like Clarion Fracture Zone, Wanderlust, Mara!, the World According to James and the Catholics consist of musicians who are to various degrees band leaders, improvisers and composers. When such bands meet to rehearse, a new piece is treated as a template from which a performance can be fashioned through collective decision-making. Each member might volunteer ideas to do with melodic tessitura, harmonisation, orchestration, rhythmic feel, introduction, coda, interludes and other structural considerations. These collective decisions can change from gig to gig. One of the products of this shared decision-making is a sense of trust in the ability and desire of other members of the band to faithfully realise a composition in performance. With this trust comes an acknowledgement, even a desire, that it can turn out differently each time.

Much as I love this form of music-making, it has never supplanted my appreciation of carefully planned composition, with a single composer's evolution of ideas and overarching design for a piece. The composition of a written score, conceived completely separately from the eventual performance, gives the composer time to consider the architecture and balance of a piece which is simply not possible when a number of minds combine to improvise a complete piece. Composition affords the luxury of reflection and revision, as well as large-scale design. The discipline of improvisation is dictated to by the tyranny of real-time, where the pen cannot be taken off the paper until the piece is finished, so to speak.

I often wonder what it is about improvisation that makes it so alluring. I have heard many people claim it has something to do with the unique interaction between performer, audience, time and place. I am consistently surprised by the discrepancies between what I intend to play in an improvisation and what actually occurs. I am convinced that this is a result of the atmosphere of a venue, the mood of the audience and the other players, as well as what they play. This palpable synergy of these elements makes each improvised performance unique and can create an incredibly heightened level of engagement. To me, this immediacy can make up for any inadequacies in structure or musical detail when analysed in the cold light of a recording.

At the same time, improvisation is ideally suited to infinitesimally subtle details in dynamics, timbre, rhythm and style which would demand daunting complexity, were a composer to attempt to notate them. Even then, the spontaneous abandon with which such details can imbue the performance can be very difficult to attain when reading complex notation. In any case, some of my favourite moments of legendary jazz recordings are those where a performer has striven to attain a musical idea and failed. Miles Davis's split notes and John Coltrane's squeaks somehow epitomise both the nobility and frailty of the human condition. Improvisation is about as human as you can get. It can provide an open window into a performer's soul.

For decades, the seemingly (to me) incompatible strengths and aesthetics of written and improvised music had kept them separate in my mind. My desire to combine my enthusiasm for these disciplines was the impetus I needed to start composing in earnest, undertaking a Master's degree at Sydney Conservatorium of Music. Towards the end of that degree, I decided to write for the same forces used on an ECM album, by reeds player John Surman, called Corruscating. In this album, Surman writes for himself and his double bass player mainly as improvising jazz musicians, accompanied by a string quartet which serves a dual purpose as a harmonic bed for their solos, and as an independent unit for which Surman wrote a series of lyrical through composed movements.

In my suite Across the Top (video on Youtube), I wrote for the same instruments, aiming to expand the role of the string writing to incorporate substantial development. I fashioned melodies which seemed equally suited to (written) motivic development, as well as improvisation. The idea was to incorporate these two streams of development side by side. When I asked my friend Ollie Miller (cello) to help gather a string quartet to play my music, he suggested a unique group he belonged to. The NOISE is an improvising string quartet with several albums to their credit.

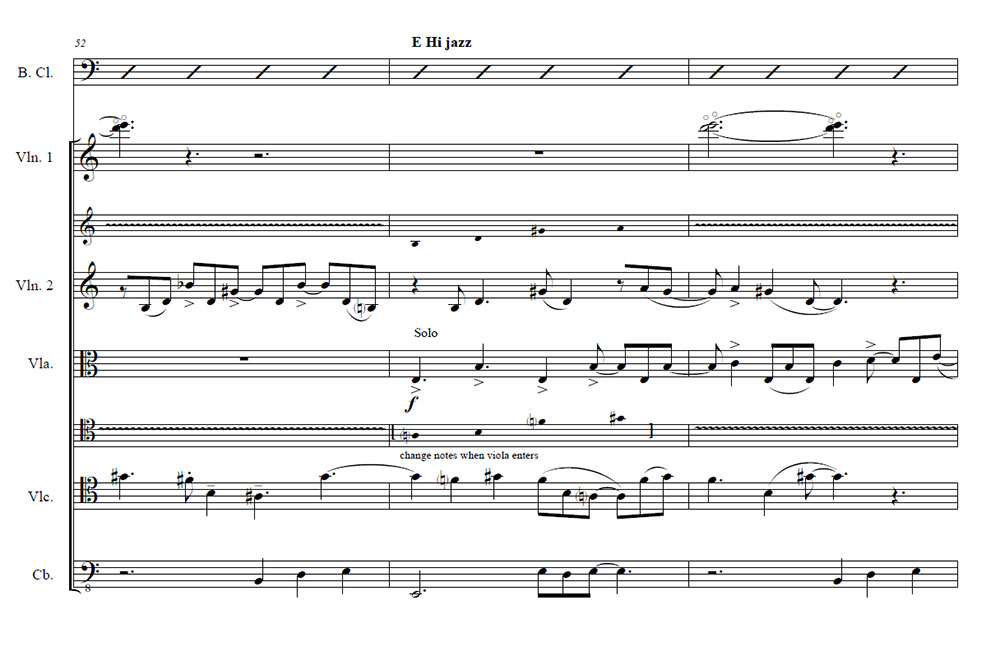

As I started working with the group, I realised these players could contribute a lot more if I incorporated opportunities for them to contribute their ideas to the musical flow. The result was a composition in which about 85% of the detail is written and fixed. This required decisions about how the piece was to play out and how the variability of the improvised elements could contribute to and affect the final performance.

View music example in larger size.

While each movement has a fixed form with a known ending, improvisation is employed in a way which can vary the dissemination of its material from performance to performance and help focus its impact on an audience. An example of this is Veronique Serret's violin solo over a Balkan Paiduschko beat in the second movement 'Lost Souls'. Her arresting style and virtuosic flare invariably gives a thrilling climax to this movement.

Passages of improvisation are placed at points where a personal response to the material helps to propel the musical discourse forward. As I became better acquainted with the personalities and skills of each player, I revised Across the Top to accommodate them. The introduction to 'Lost Souls' (watch a Youtube video) is a result of a few instructions for the players to improvise on the harmonics of the A string or the note E, while violist James Eccles plays a few wisps of the movement's main melody. The result is a still, eery, arid soundscape. When cellist Ollie Miller joined in with Brett Hirst's solo bass cadenza (watch a Youtube video) part way through 'Gibb River Road' during a rehearsal, the dynamic of the dialogue was so exciting that we decided to keep it.

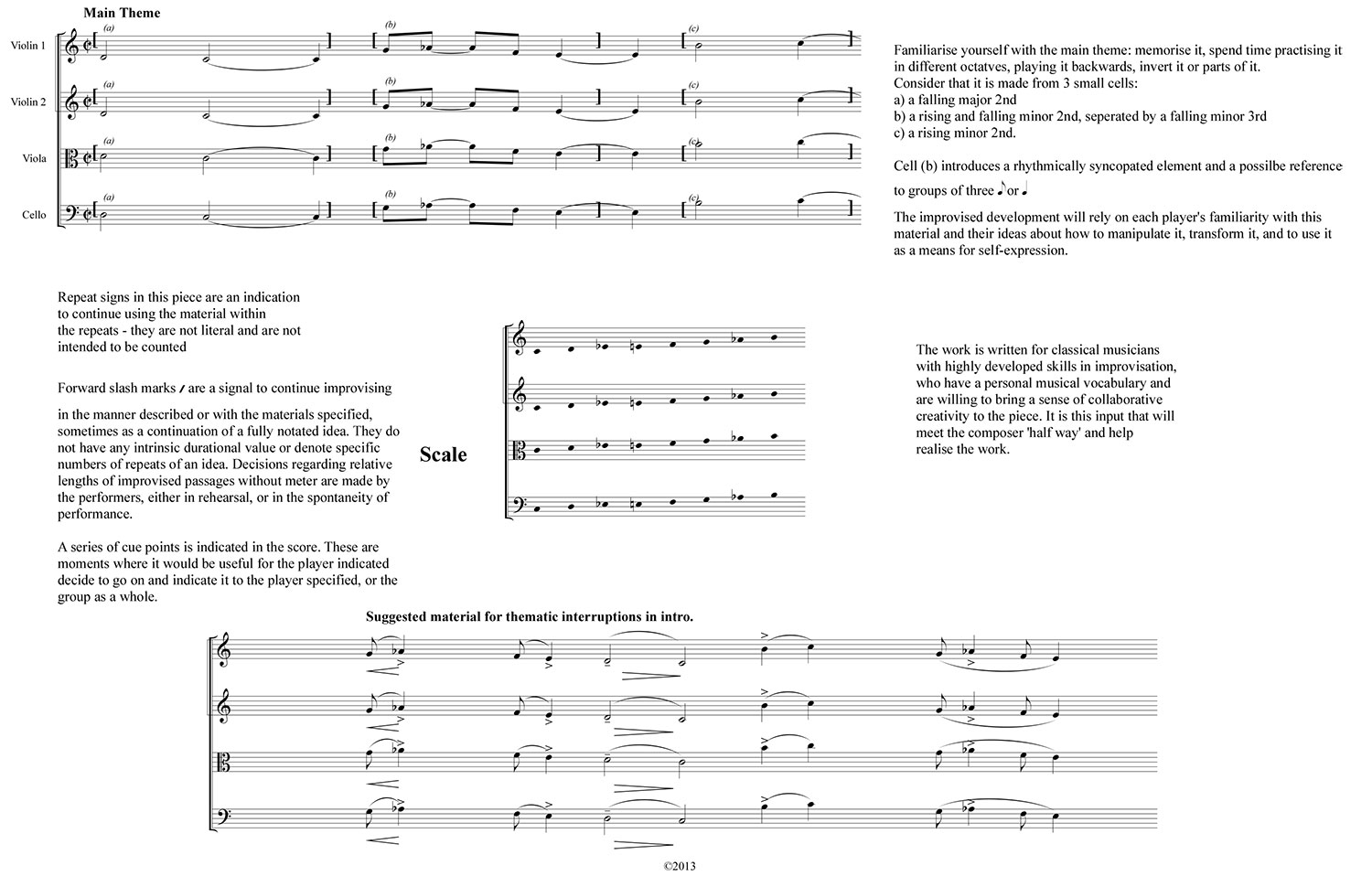

When The NOISE commissioned a new string quartet from me as part of their double album Composed NOISE (see also: NOISE website and shop), I decided to entrust a greater share of the musical substance to their skills and sensibilities as improvisers. Merge Emerge gives each member of the group solo and group opportunities to interact with and develop the material in the piece. A key to success in writing for improvisers comes from knowing the players and their strengths, as well as having the faith to relinquish control over at least some of the parameters of the piece. Jazz performers do this naturally and with complete faith in the success of their music. I guess this is a large part due to jazz improvisation being a current, living performance practice.

When it comes to incorporating improvisation into contemporary classical genres, it helps to have something of a personal knowledge of individual skills and a willingness to collaborate. At the same time, the performers need to be familiar with the materials being manipulated in the piece, so that their improvisations bear some relationship to the notated tonal and motivic elements. In Merge/Emerge I set these out in a preface page (see below, and here in larger format).

Another attribute required of the composer is the willingness to accept that the final score of a piece for improvisers is not complete. The composition cannot be fully analysed, based on the written product alone. Any work which employs improvisation can only be assessed in the process of realisation. This may sound like a disadvantage or a creative compromise. Perhaps it is more indicative of a different aesthetic or philosophy on music-making. My desire is that this delegation of authorship and creative responsibility can give performers more of a sense of personal investment in a work. In the case of Merge/Emerge, I tried to reflect this by registering each of the performers as a partial copyright owner. If other groups decide to perform the same piece, I offer to register each new group performance as another version for royalty purposes. This could become a cumbersome process, but it will suffice until I can think of a better method.

When writing music which incorporates improvisation, the motivation and aesthetic behind its use is an important consideration. It is easy to confuse improvisation with chance or multiple-choice. When specific parameters are not important in a piece, a composer can put a bunch of notes in a box and ask performers to pick any of them to play, for instance. Personally, I feel improvisation is a chance for a performer to put something of themselves into the piece by making active creative choices. The materials I offer are very similar to the 'notes in a box' scenario. I rarely if ever stipulate anything regarding rhythm. I have to admit, I give the bare minimum of direction or parameters to improvisers. I guess this is because I assume a certain level of familiarity with various styles and performance practices. Much of my music relies on rhythmic propulsion or 'groove', so I seek performers who know how to harness these attributes in their own playing.

I believe there is enormous potential for more classical performers to adopt improvisation into their everyday music-making. Having worked with The NOISE quartet I have met quite a few classical players who have developed diverse skill sets and are at home improvising in various styles. When one considers the volume of repertoire an orchestral musician learns over their career, the breadth of tonal and rhythmic vocabulary available for them to create with is staggering. The missing link to becoming an improviser in most cases is a sense of permission, to experiment, to change and adapt. That takes courage and self-belief.

AMC resources

Paul Cutlan - AMC profile (biography, works, events, recordings)

Across the Top / Paul Cutlan, Brett Hirst, The NOISE (Tall Poppies 2015) - listen to audio samples and purchase the CD from the AMC Shop

Further links

Paul Cutlan - homepage; listen to Cutlan's work Cosmic Linguine (2014 - Soundcloud); watch and listen to Cutlan's work Affirmations (2014 - Vimeo)

The NOISE - homepage (http://thenoise.com.au/)

© Australian Music Centre (2016) — Permission must be obtained from the AMC if you wish to reproduce this article either online or in print.

Comments

Be the first to share add your thoughts and opinions in response to this article.

You must login to post a comment.