21 September 2016

Insight: the Hour of the Flute

Physicality, expressivity, and energy

Image: Dominik Karski

Image: Dominik Karski © Marek Suchecki

Writing for flutes has been evolving into a major thread in my composing for more than a decade. This has been possible thanks to having the honour to collaborate with some of the finest flautists specialising in new music, including Ewa Liebchen and Rafał Jędrzejewski, who make up a Warsaw-based duo called Flute o'clock. In June this year, Polish new music label Bôłt Records released a CD, entitled Glimmer, with all my flute works to date, recorded by the duo. In total, an hour of flute music. In this article, I attempt to highlight the key areas of my compositional thinking while reflecting on the works included on the disc.

I have always been interested in long-term and in-depth exploration of instrumental possibilities, and I have found that this can be realised most effectively through ongoing and close collaboration with performers. Looking at the Glimmer CD, I see quite a bit of hard work done over the years. Along the way, however, the flautists and I have also found much pleasure in experimenting, discussing ideas and possibilities, and wondering 'what if?'. We have learnt and drawn inspiration from each other through working on each project slowly, over an extended period of time. This has proven to be a reliable way to immerse ourselves in the ideas investigated, so that the creative journey is experienced meaningfully.

© J. Wojno-Wolska

The journey starts with considering any possible physical actions that can be applied to the instrument, without categorising resultant sounds according to the division into those produced with the classical technique, and 'effects' that emerge through so-called 'extended techniques'. Articulations such as multiphonics, microtones, tongue-ram, key percussion, pizzicato, whistle tones, and many others have been utilised for many decades, so today they can no longer be thought of as additional special effects. They all constitute the vocabulary of contemporary musical language, with each sound being unique and having its own expressive quality. All it takes is to think of the instrument and envisage the possibilities that are just there, available to be used.

When thinking of the technique of sound production on the flute, the basic elements needed are air stream, fingering, and mouthpiece position. These are all physical operations that can be zoomed into and explored in greater depth. For example, air stream can have different pressures and can involve various tonguing articulations, which, in turn, can be used independently without any air; fingering, when considered on its own, opens up an array of percussive sounds of the flute's mechanism; mouthpiece position is an incredibly flexible technique, as it affects the sound quality directly, with many possibilities from pure and solid pitch to the most subtle and fluctuating shimmers. The list of possibilities is extensive and additionally enriched by merging the instrument with vocal/mouth/throat articulations, but the essential point is that the searching occurs at the level, where the focus is on individual components of sound production before a concrete sound object is formed. It is therefore the process of formation of the musical substance that is articulated, because exposing the components means avoiding congruence between them (if they're congruent, more concrete sound objects are formed).

The beginning of this way of compositional thinking dates back to Glimmer written in 2002. It was the opportunity to have it performed in Amsterdam the same year that contributed to writing further works with the aim of examining more closely the expressivities of various physicality components of the flute technique.

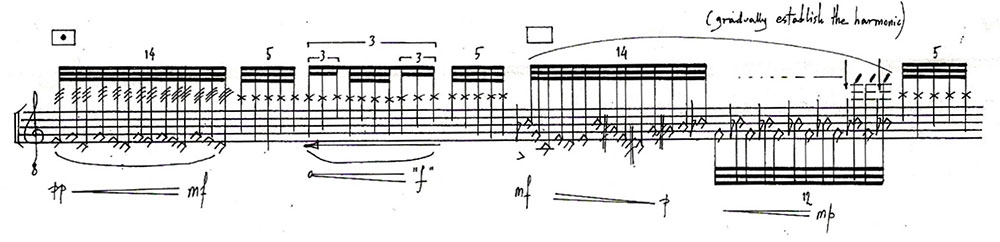

Glimmer (2002, for alto flute and bass flute) - view music example in larger size.

The works composed shortly after Glimmer, i.e. two bass flute solos Streamforms and open cluster M45 (2003), expose a number of physicality components much more. Writing these works was a major step towards thinking about sound production as the initial source of the musical material, with its physical aspect being focused on very closely in order to bring out the distinct expressive qualities of a wide variety of sounds obtainable on the instrument.

Every sound, even as minute as a key click, has an innate and unique expressivity. Thinking about how flute technique works in physical terms leads to greater awareness of the expressive properties of sounds. When different physical actions interact, the expressivity of the sounds also carries an emotional charge, as it is a natural element of expressivity. The emotion can be magnified through the focus on the physicality of sound production.

Streamforms (2003, for amplified bass flute) - view music example in larger size.

In order for the performer to bring out the expressivity and the emotion, it is the physical actions (not always the sounding results) that are notated. Since flute technique often involves combining operations that produce unstable and unpredictable outcomes, it's not always possible to notate exactly what will be heard. Therefore, the precision and specificity of notation applies to physicality. The search for the musical material based on focusing on the components of sound production does not always involve knowing exactly what the sound will be. Rather, it is driven by the curiosity of finding out what the sounding result will be. The score is not really a representation of the sound world, but more an instruction manual for the performer to apply specific physical operations to the instrument. The performer can use these instruction manuals in a way that allows them to explore the physicality of flute playing and develop their own interpretation of the musical work. Whatever the interpretation, the essential character of the piece will remain unchanged, because the precision of notation establishes a particular sound world and musical process.

Open cluster M45 (2003, for amplified bass flute) - view music example in larger size.

At the time of writing the bass flute solos, thinking about the physicality of producing sound and breaking it up into components also suggested the idea of using an analogous method in relation to the whole compositional approach. By the time the work on the first commission from Flute o'clock began (Veiled Voice, 2011-2013), generating the musical material had become divided into separate layers: tempo, rhythm, physicality (articulation, and the addition of voice), dynamics. Each layer is focused on individually, sometimes written out on its own from beginning to end. By the same token, one instrumental part is completed in its entirety before the next one is begun. The musical substance is gradually put together by adding the individual layers. The important realisation that emerged out of this method was that complete control over the large-scale form was no longer in place. But there was no absence of control either. It was therefore all about remaining BETWEEN having control and giving up control.

The layering method can be described metaphorically as a process of weaving a veil, semi-transparent, and then weaving another and placing it on top of the first one, then another and another, always overlaying the veils. The remaining BETWEEN is always in place, since the ultimate result is not known until the final veil has been placed. Only then can the complete image be observed, as the whole process leading up to it is guided by the search for that image.

The essential purpose of navigating through the control/no-control balancing act towards a final result which is not fully known is that it creates the possibility of finding musical processes that unfold in a coherent, yet unpredictable way. Like a stream, the music can evolve in an organic manner, remaining consistent and yet fresh at each moment. Transition is the governing principle.

The musical substance in Veiled Voice incorporates the use of vocal sounds, but it is not the voice that is the main focus, but the veiling, as it generates various manifestations of transition. Voice is a medium that conveys emotional expression more directly than an instrument, and this very directness is covered by the veils of transition (the concrete versus the abstract). As the work progresses, it explores the interactions between the two areas, and in doing so forms a story about the nature of transition and the value of direct expression.

Veiled Voice (2011-2013, for two amplified flautists) - view music example in larger size.

On the way to Veiled Voice, a solo flute miniature was written in 2009, 112 Iphigenia. The title refers to the scientific designation of an asteroid, which is named after the character from the Greek mythology (similarly to open cluster M45 referring to the Pleiades). Despite its short length, 112 Iphigenia was a very important step in investigating musical instability through change, from gradual transition to sudden contrast.

112 Iphigenia (2009, for amplified flute) - view music example in larger size.

The next work commissioned by Flute o'clock, Veiled Words (2013, for two alto flutes and two tam-tams), came out of an interdisciplinary project entitled Between them and eternity there was but a minute and a half developed on the basis of two literary works: Italo Calvino's essay Quickness and a short story by Thomas de Quincey, Visions of Sudden Death. Echoes of these works resonated during the process of writing the score, especially with regards to the ideas of quickness, suddenness, and unexpectedness. In his story, de Quincey focuses on an event that lasted a minute and a half, and its account unfolds over dozens of pages - a minute and a half, or an eternity?... Calvino's essay is an instalment of what was meant to be a series of six lectures, but sadly, the author passed away before writing the sixth one (which was to be called Consistency). The collection of five lectures was published under the title Six Memos for the Next Millennium.

In Veiled Words, a few shards of de Quincey's text are spoken through the instruments, while the general swiftness of the flutes is set against drawn-out pulsations of the tam-tams (played by the flautists with foot-pedals). Suddenness and unexpectedness (flutes) against the unaffected tolling of distant bells (tam-tams).

Veiled Words (2013, for two amplified alto flutes and two tam-tams) - view music example in larger size.

Thinking of the instrumental physicality very precisely through specificity of notated articulations is very necessary in learning about the available sounds and their expressivities. What is equally essential is the specificity of rhythmic notation - not just for the purpose of fixing events in time, but a desire to understand the structure of coherent yet unpredictable flow. The interest in the concept of flow is related here to natural phenomena and some aspects of chaos theory, and what is most inspiring about it is both its beauty and complexity.

However, rhythmic complexity can be built on a simple basis. To cut a long story short, using the basic rhythmic values from crotchet to demisemiquaver and subjecting them to the most common subdivisions creates twenty-eight different rhythmic durations within a crotchet beat. What is most important about this is the tiny differences between the durations, as well as the fact that there are so many options within the narrow space of a crotchet. Understanding the smallest possible differences is vital for building musical flow that unfolds organically and has elasticity within its temporal dimension, as it remains consistent yet changing.

In my work, rhythm is the most fundamental musical element. It is the spine of music. Rhythmic design shaped through precise choice and specificity of notation opens possibilities of perceiving time in different ways. Rhythm is the means by which energies are formed and become running musical currents.

The metaphor of ever-flowing stream has been an inspiration for a number of years, beginning with the large ensemble work Streams Within (2002-2003, with Glimmer being its integrated part). Since then, the learning about the structure of change has continued. Change is about remaining in the process of becoming - rather than the state of being - and is perceived as having a very logical and natural mechanism that functions through transition. The great flexibility of the flute is perfectly suitable for these explorations, and it is the focus on the components of flute physicality that has created a direct link to understanding the building blocks of transition.

Streamforms III (2015, for flute, alto flute, and harp) - view music example in larger size.

The ideas behind

Streamforms III (the latest work on the disc, Flute

o'clock with harpist Zofia Dowgiałło-Zych) have to do with

turbulence as a meeting of coherence and unpredictability

manifested through energies that weave their way from one moment

to the next, perpetually renewing themselves and remaining fresh

at each successive step. The aim was to present turbulence as an

interplay between stability and instability, between retaining

control and giving it up in order not to lose the freshness of

the sounds' energies. These ideas are by no means exploited to

the end. The main project for 2016 is a work for alto flute

commissioned by Carlton Vickers, and more Streamforms

are planned for the near future.

> This article forms part of a series of 'Insight' feature articles by the AMC's Represented and Associate artists.

AMC resources

Dominik Karski - AMC profile

Glimmer: Dominik Karski - Flute O'clock - CD details and sound samples - AMC Online

Further links

Dominik Karski: Glimmer - Flute o'clock - Bôłt Records

Dominik Karski - SoundCloud

Flute o'clock - homepage

© Australian Music Centre (2016) — Permission must be obtained from the AMC if you wish to reproduce this article either online or in print.

Comments

Be the first to share add your thoughts and opinions in response to this article.

You must login to post a comment.