20 August 2024

Shaping a new percussive reality

Constructing accurate playing directions for untuned percussion through a simplified and standardised notation: the first step

Image: Ryszard Pusz

Image: Ryszard Pusz The issue

Notation of Western music is incompatible with the expression of music in untuned percussion, effectively muting its voice. It is time to re-align the score.

The notation system is predicated upon the premise that each particular action will replicate the same result, in this case, the sound, which can be documented with the one symbol - a note. For instruments of 12-tone tuning this is an effective method of imparting playing directions - beautiful in its simplicity. However, when that particular action, depending on where it is directed on the instrument, what implement is used, and what type of action is employed, can elicit one or two of up to 20 characters of sound, not one of which is aligned to 12-tone tuning, the notation fails.

How this incongruity came about is a fascinating quirk of history.

Since Strungk's infusion of local colour using cymbals in his opera Esther (1680) and Handel's military reference on snare drum in Joshua (1747) composers have introduced, for specific effects, percussively-generated sounds. These sound sources have been imported from a variety of cultures, genres and playing contexts; and then the medium was confused by the inclusion of a miscellany of also 'untuned' aerophones and chordophones such as bird calls and berimbaus. In the process there has been little appreciation of the full nature of those sound sources or their musical potential. Indeed, faced with such a multiplicity of imports, in nonstandard diversity, composers have just continued the idea of the instruments providing specific 'effects', and percussionists have focused on the 'right', or traditional ways of playing them.

Consequently, these sound sources, over 100 in number, have been grouped together into one mass called 'untuned percussion', and inaccurately designated as individual instruments that are singular in concept and assumed to be mono-tonal in character -a total misconception. Little regard has been paid to the potential depth of intensity in their musical voice. And attempts to adapt traditional notation to the medium have been ad hoc, localised and piecemeal, increasing the imprecision of notational direction.

This has led to unsatisfactory playing terms and conditions of application, which include:

-

Five notational systems, each of limited

application, forcing composers to choose which might best

convey their musical intent, and compelling players to learn a

new set of concepts and applications for each piece;

-

Gross overuse of the symbol 'x' across a disparately

wide sweep of playing directions, depriving the symbol of any

notational validity;

-

Uncritical acceptance of playing directions from other

contexts as the norm for untuned notation, reinforcing the

misconception of instruments as providers of singular effects

only, rather than complete musical entities;

-

Limited and inflexible MIDI audio files of individual

instruments, preventing composers from hearing the

totality of possible instrumental sounds; and

- Continued piecemeal development of new symbology, with glyphs, symbols, particularised extensive legends and written directions all initiated in local contexts, thus denying any possibility of universalising playing directions.

Under the weight of these conditions, the distinctive voice of untuned percussion has been muted, denying it and the greater music art form of appreciably deeper harmonic presence and expression.

The instruments

Untuned percussion as a musical medium is defined by the following conditions:

1. All the instruments come in a range of sizes. This ignored fact is significant as the instruments, despite being 'untuned', have distinct differences of 'pitch'. So, the names historically allocated to them are effectively concepts of those sounds; and compositions need to more accurately indicate the type of sound. For example, 'High', 'Medium', or 'Low" snare drum, or a ranking of sd1 (highest) to sd6 (lowest) could perhaps better convey the harmonic intent of the composition; and also be placed in an appropriate position on the stave. Moreover, the accepted categorisation of the instruments under their materials of construction, being skin, metal and wood, need to be understood as conceptual typologies of sound, based on both their materials of construction and, just as importantly, methods of playing. This necessitates the expansion of those typologies as explained under the section 'Conceptual typology'.

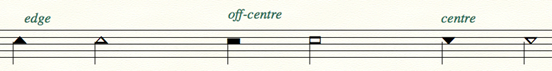

2.Within the instruments there is also a range of sound characters depending on where the instrument is struck, the type and part of beater used, and the manner of playing. From each drum for example, three characters of sound can be elicited by playing on the edge, off-centre, or centre of the head; three more on the rim when played with neck, shoulder, or shaft of snare drum stick; and a further three when combining rim and skin sounds (rimshots). Using felt beaters, wire brushes, fingers or fingernails introduce further complexities of sonic character; and these are nuanced even more when using different playing actions such as a side-to-side tremolo, or smooth glide across the head with nails or brush.

3.The instruments can be played either as discrete entities or in varying numbers of homogenous or disparate combinations of traditionally recognised instruments, altered states of those instruments, or any resonant material. The implications are broad-ranging and cannot be underestimated. If the essential qualities of the instruments are to be indicated in multi-percussion compositions, each instrument must be fully and clearly notated within one space or line on the stave. And only in this way can the notation be standardised, for multi-percussion pieces to be more easily learned, and comprehended harmonically.

Herein lies the challenge.

A new notation

Accurate notational playing directions for untuned percussion must incorporate these conditions and characteristics of the instruments.

To develop such a system of notation, I have devoted the last four years to rigorous and concentrated experimental research of the issue. The work was guided by two principles - how to make the notation convenient for composers to apply, and easy for players to read. And it was inspired by innovations initiated by Milhaud, Colgrass, William Kraft, Sculthorpe and Stockhausen.

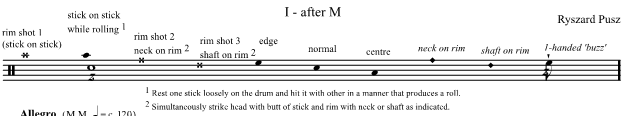

The impetus came from a snare drum work I wrote that revealed the shortcomings of the current system. Notating multiple ways of eliciting myriad sounds, it required intricately detailed legends for every movement, each of which exhibited singular manners of playing to evoke different characters of sound. However, the notational directions were particular to each movement, suggesting that any further complications, such as combining the elements into one movement, would be beyond the reach of the current notation (see Fig. 1). Specific playing directions of any greater complexity, such as indicating fast interchanges between types of sound, would require large or multiple staves, or a clumsy set of written instructions - both in conflict with easy reading of the music. And it is doubtful that the playing directions in this work, or indeed in any piece, could be universalised when using traditional notation.

Fig. 1 Legends for each movement of Suite for Snare

In fact, the situation necessitates development of a standardised notational system that can easily indicate instrument types as well as particular instruments. Such a framework would still allow for individual organisation of multiple-percussion setups, and through a standardised notation system be universally easy to read, eliminating the need to wade through disparate sets of playing instructions that apply only to specific pieces.

Conceptual typology

This requires firstly ordering these instruments of diverse sizes and 'pitches' under materials of construction and methods of playing, placing them in four conceptual typologies:

1. Membranophones: drums of classical, jazz, popular and folkloric music;

2. Metal idiophones: triangles, cymbals, tam-tams, gongs, cowbells, anvils, metal pipes and plates, thunder sheets, and lithophones;

3. Wooden idiophones: woodblocks, temple-blocks, log drums, marching men, clapping sticks; and

4. 'Frictophones': shakers/scrapers (maracas, cabasas, guiros, cuicas, sandpaper blocks), rainmakers, ocean drums, flexatones, ratchets; sirens, wind machines, wind chimes; castanets, bullroarers, thunder tube / spring drum, bells, and whistles.

'Frictophones' (my word) are instruments of diverse construction materials, or whose method of sound production is via a form of friction within the instrument, as seen and heard, for example, in wood, metal, rawhide, plastic or rattan maracas.

As well as reading the pitched

notes of marimbas and timpani, percussionists also need to

recognise disparate instruments of the untuned family by their

position on the stave, often reading the music from a distance.

And the type and number of these untuned instruments and their

placement in the score varies across different pieces of music.

Standardisation of this element of music creation is urgently

needed.

As well as reading the pitched

notes of marimbas and timpani, percussionists also need to

recognise disparate instruments of the untuned family by their

position on the stave, often reading the music from a distance.

And the type and number of these untuned instruments and their

placement in the score varies across different pieces of music.

Standardisation of this element of music creation is urgently

needed.

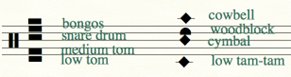

This is especially the case if the piece entails fast-moving or frequent interchanges between different instruments or beaters, and even more when sight-reading. It is important to note that the organisation of multi-percussion set-ups is in layers with the drums as the base layer and the others above or below. So, as a general rule, I believe it to be an effective playing direction to notate the drums in the spaces and metals and woods on the lines. Frictophones, usually played as discrete items, can be placed anywhere. Notating the instruments this way reflects this separation and makes the music easier to read.

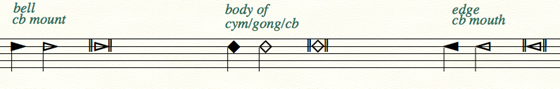

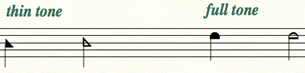

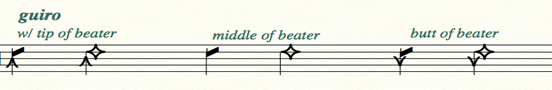

The most efficient way to ensure ease of reading is to create new noteheads; and then allocate particular shapes to each set of instrumental concepts. Determining a logically consistent set of note symbols within each concept can facilitate easy recognition of sounds and tone colours elicited at the edge, off-centre, and centre of the instruments. It enables each instrument to be notated within one space or line. Applicable to all pieces it will provide a further level of standardisation to the notation, and enable easier learning of the repertoire.

Importantly, the system is firmly centred on evoking the totality of acoustics in the instruments solely through clear and simple notational direction in order to cater for and unveil the magnitude of their distinct modes of musical expression. Simplified playing directions, also usable with tuned percussion, readily and consistently identify:

- Which particular instrument is to be played in all multi-percussion set-ups;

- What part of the instrument will elicit the specific musical effect;

- Which beater is to be used;

- What part of the beater will produce the particular sound;

- Which distinct articulation is relevant to each instrument and playing context; and

- What manner of playing will evoke the composer's musical intent.

Basic note shapes

This new system of notation delivers accuracy of easy-to-read playing directions. A minimal number of notehead shapes indicate the area of the instrument on which to place the stroke, or type of sound to be elicited. Where those notes are placed on the stave will indicate their 'pitch', relative to the other instruments in the composition (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Basic note shapes

Membranophones

Membranophones

Metal idiophones

Metal idiophones

Wood

idiophones

Wood

idiophones

Frictophones

Frictophones

However, the details of the sounds elicited are more complex than just a 'pitch'. The character of sound produced is determined by the type of beater that is used; and this is further nuanced by the part of the beater employed to elicit that 'pitch'. In other words, each particular sound is an amalgam of all three elements of:

- Area of stroke placement;

- Type of beater; and

- Particular part of the beater used.

Articulations

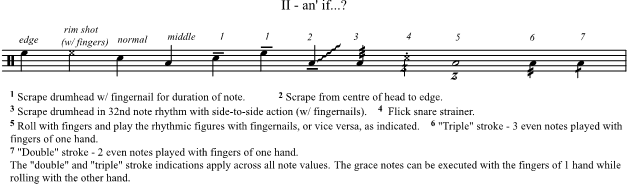

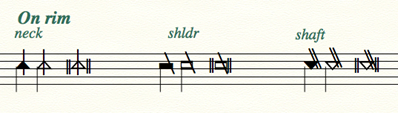

Where necessary, note shapes designating the area of stroke placement would be augmented with symbols indicating articulation particulars. The same articulation markings can also be used for the tuned percussion instruments (see, as an example of this, Fig, 3).

Fig. 3 Playing on the rim using the neck, shoulder or shaft of the beater

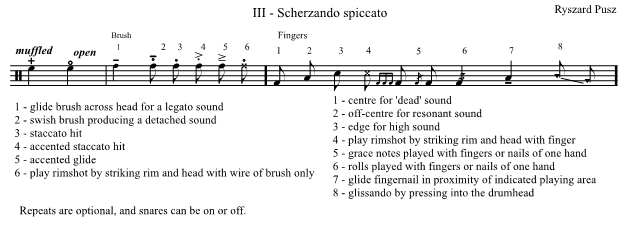

To ensure logical consistency of operation, these articulation markings of beater specificity are used across the whole percussion medium. Other articulation markings, such as staccato, legato or tremolos are placed above or below the note, or on the stem, as seen in these détaché strokes played with the brush (see Fig. 4), and fingernails legato strokes (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 4 Détaché brush strokes at the edge of the drum

Fig. 5 smooth off-centre legato strokes with fingernails

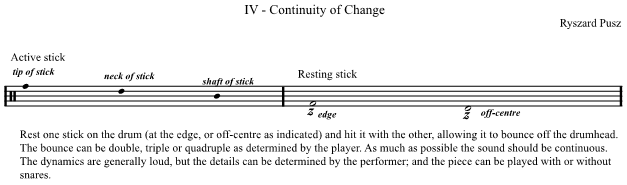

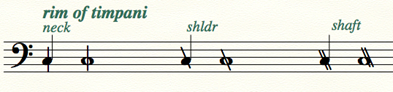

A much-ignored but significant element of articulation relates to the notation of tremolos, commonly referred to by percussionists, as 'rolls'. Looking past traditional modes and contexts of playing them, on most instruments a diversity of tonal colours and characteristics can be elicited, depending on whether one is playing single, double, triple, or quadruple-stroke rolls. They can be more accurately notated by using the following symbols (see Fig. 6).

Fig. 6 Two ways of notating Single, Double, Triple, and Quadruple-stroke rolls

General tremolos can also be notated (see Fig. 7).

Fig. 7 Showing General Tremolo, as played with straight and side-to-side actions

Further sets of articulation markings for eliciting distinctive tonal qualities of the instruments, and the playing actions that expand the technical armoury and modes of execution, are elaborated on and explained in my manual Shaping Percussion Notation.

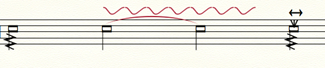

So, if a system denotes clearly which instrument is to be played and which area is to be struck by the shape of the notehead, and the manner of playing is indicated by a standard set of articulation markings, each instrument can be notated within one space or line. And the legend will only need to indicate positioning of the instruments on the stave (see Fig. 8).

Fig. 8 Legend of possible instrument placement on stave showing relativity of 'pitch'

In conclusion, this purposed system of accurate notational symbols with articulation details is the first step towards creating a dedicated untuned percussion digitised font. If accepted by players and composers it could unveil the range of percussive sounds, and standardise accurate playing directions that are easy to read. Notation that builds on the intricate relationship between instrumental characteristics, beater varieties and manners of playing to express its music can enable the medium to flourish. This, in turn, could enhance the greater music art form with appreciably deeper harmonic presence and expression - an ambition worthy of pursuit.

© Australian Music Centre (2024) — Permission must be obtained from the AMC if you wish to reproduce this article either online or in print.

Ryszard Pusz is a percussionist and composer currently researching new parameters of percussion composition, performance and presentation. Exploring uncharted sonorities of the medium and purposeful interpretations he continues to develop unique playing techniques and theatrical approaches.

Comments

Be the first to share add your thoughts and opinions in response to this article.

You must login to post a comment.