17 October 2017

There are composers, and people who compose

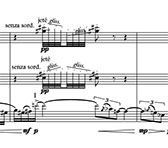

Image: A minute detail from Kerry's String Quintet no. 2

Image: A minute detail from Kerry's String Quintet no. 2 Art music practice in today's Australia is a rich and diverse field, and pathways to the profession via education and further professional development are fluid and varied. The language we use, on the other hand, doesn't accurately reflect our contemporary practice. We also need to be able to communicate effectively with those outside our sector.

This is why the AMC is commissioning a series of articles about being a composer today, for publication over spring and summer 2017-2018. We're calling for new, bold and positive definitions and redefinitions of the word 'composer' in our contemporary context. We invite you to respond to these articles with your commentary, here in Resonate, and on social media.

Two articles, by Gordon Kerry and by Jim Denley start the series [more articles listed down below]. See also responses by Rhys Gray (Resonate) and Andrew Ford (Inside Story).

One of Australia's leading composers and I were chatting a while back, about one of Australia's leading performers who had taken to calling himself a composer, though not - not yet, anyway - one of Australia's leading ones. My colleague's sage summation was 'you know, there is a difference between a composer and being someone who composes.' Now, of course, the division of labour that produced the 'professional composer' - someone who essentially does nothing but write music - is a recent and fairly arbitrary thing. After 1785 Mozart suddenly performed less (and composed more substantially), possibly owing to arthritic fingers; Beethoven's deafness precluded him from performing from the early years of the 19th century; Schumann famously injured his hand. But, these anomalies aside, until well into the past century composers would also routinely perform as conductors, soloists or accompanists, and then, as today, full-time composers might very often also be teachers, arts administrators, broadcasters or writers. While Mahler, Richard Strauss or Britten were brilliant conductors, however, it's not for their conducting that we remember them; the late Pierre Boulez is revered as a composer by those of us who love nasty modern music, but as a conductor by fans of Wagner as much as the second Viennese School. Let me draw you a Venn diagram.

Don't get me wrong: I am all for composition. I love it. And I think that all musicians should be schooled in whatever techniques will allow them to be people who compose. (I say 'schooled' but this can mean anything from formal instruction to informal mentoring.) There are many more university places for undergraduate composers than when I was a student, and I certainly don't think that's a bad thing, even if only a tiny percentage will become professionals. As composer Mary Mageau once said at a conference I attended: 'creativity is a human right'. Moreover, those students that end up teaching may be called upon to write music for didactic purposes, those that end up professional players may, through having learned composition, have a greater insight into the music that they play. Beethoven once reportedly said he could have given Napoleon a run for his money as a military strategist, and, while not wanting to push that analogy too far, it is true that composition is strategic, requiring the tweaking of many small units while maintaining a sense of the big picture. Not a bad life-skill for anyone, really.

But - slight pause while I paint a target on my forehead - the fact remains that some people do some things better than others. A neighbour of mine recently retired from being a GP and announced to me, only half-jokingly, that she was planning to be a famous artist. She didn't think it funny when I said I was going to retire and be an endocrinologist. (I wouldn't know a pancreas if I fell over one; she had never squeezed a tube of madder lake in her life.) Let me be clear: artistic activity is good for the artist, and the more people who do it the better, but it's rare that a fully formed professional talent will appear late in life. Not impossible: I heard a perfectly wrought work at a regional music camp some time ago, by a woman who had only taken up the violin and composition in retirement - but it's rare. Sadly, though, there is a besetting idea that to be an artist is a 'no experience necessary' job, and it besets the profession within and without. The fact is, though, to compose a work of substantial scale, be it something for the stage or a large-scale instrumental or orchestral piece, or, I daresay, a complex work for electronics, requires skill, patience, experience, and talent.

There are, of course, composers who have flourished after establishing themselves as a preeminent instrumentalist - look no further than Brett Dean or Ian Munro, and indeed those like Elena Kats-Chernin who has progressively increased her profile as an interpreter of her own work. But of late I have come across several examples - and not necessarily among Australian musicians - of work by performer-composers that relies more on the celebrity of the player than the inherent interest of the music. And yes, Virginia, there is such a thing as inherent interest…

There is nothing new in this - for every Liszt or Paganini there were any number of ephemeral virtuoso-composers. The music to which I refer would almost certainly be deemed pleasant and totally unoriginal background music were the composer to remain unidentified; as it is, it represents a non-threatening programming option for presenters. Not that there isn't a place for such music, and not that everything should or can be a masterpiece. But nor is every work of art, no matter how sincerely meant, equal. OK, the division between 'composers and people who compose' might be overstating it, but I think we should be looking for originality of musical thought (which is not to prescribe style) and the ability of the artist to think on both an expansive scale with an ear for fine detail, to produce an event unique in the audience's experience. Sometimes you need to call in a professional.

Other articles in the series

Jim Denley: 'We Compose' (Resonate 12 October 2017)

Cat Hope: 'What it means to be a composer today' (Resonate 11 December 2017)

Cathy Milliken: 'On composition' (Resonate 29 January 2018)

© Australian Music Centre (2017) — Permission must be obtained from the AMC if you wish to reproduce this article either online or in print.

Comments

Add your thoughts to other users' discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

The only societally meaningful definition of composer

by Frank Mangeim on 23 December, 2018, 4:25am

"A composer is one who communicates through music"

With the universal revolution in the arts in the early 20th Century avante gardists redefined composition and artistic value to be whatever they thought it should be. Peer specialists, not audiences determined what was artistically valuable. A wall between contemporary music and music-loving audiences went up. It remains up, although in-your-face compositional styles have faded.

On behalf of the Delian Society I'd like to learn whether there are any Australian composers outside pop music today who defy contemporary arbiters of quality in music and compose to communicate. Names and email addresses please. They'll get invitations.