1 March 2008

Following the Least-Trodden Paths

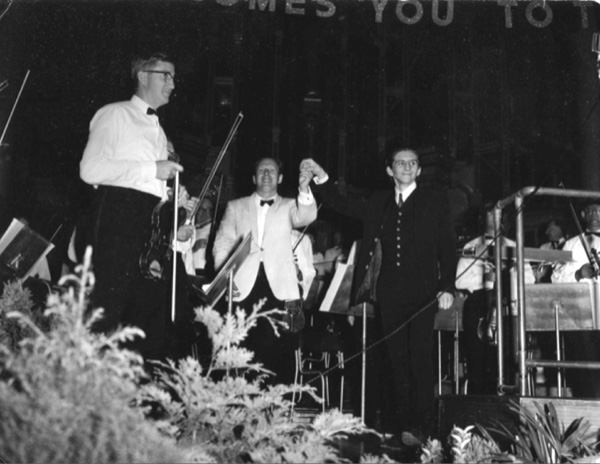

Image: David Ahern

Image: David Ahern You remember playing [La Monte Young’s] String Trio in the Round House in May 1969? Someone who was there in the audience tells me that while we were playing two rats came out from under the stage and sat listening to us.

So Cornelius Cardew wrote to David Ahern, 2 years later. The (in)famous English experimentalist kept in close touch with the young Australian upstart of a composer over the next few years as, in his words: ‘Good rumours have reached me’.

Cardew had a band of young supporters for his (‘music for the people’) aesthetic in the same way composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen and John Cage drew theirs around them, but it’s little remembered today that there was an Australian line – nay parallel – from the goings on of the Scratch Orchestra back in old Blighty.

it’s little remembered today that there was an Australian line – nay parallel – from the goings on of the Scratch Orchestra back in old Blighty. Howard Skempton, born in 1947 – the same year as David Ahern – was one of the other youngsters on stage that night in May 1969 at London’s Round House. This was the concert that led to the formation of the Scratch Orchestra, a boiling pot of experimental and communal ideas: Skempton was a founder along with Cardew and Michael Parsons.

Skempton enjoys somewhat celebrity status nowadays – in academic circles for that oh-so English strand of experimentalism in his roots, resulting in a music whose every moment feels precious; but also popularly in concert circles since the success of works like Lento, a BBC Symphony commission in 1991, and Images for Channel 4 in 1989. Following those performances, Skempton has been regularly commissioned and performed all over the world, is published by Oxford University Press, recorded on several labels and most importantly has a Facebook group dedicated to him called ‘I love Howard Skempton’.

Young English composers, especially those tired of other modernist fashions, have dug up those roots of Skempton’s. There they have found in the anarchic history of the Scratch Orchestra another interesting line of remarkably static or momentary contemporary music that can be explored, and there they begin to find their own voice, more like Skempton’s or Eric Satie’s than Michael Finissy’s or Brian Ferneyhough’s. I was one of these young composers, around the time I graduated from Exeter in 1996. My peers used to (with ample amounts of sarcasm) refer to me as the new simplicitist.

The continuation of this same line of thought in Australia is not as evident, despite the fact that David Ahern picked it up and carried it on in Sydney just as fervently (if not as successfully) as Cardew, Skempton et al. were doing in the United Kingdom.

Ahern was an enigma, and his story, if anything, is more captivating than Skempton’s. Not from a particularly musical family, he decided, at the tender age of 17, that he was going to pursue a career as a composer of the most modern music, and door knocked Nigel Butterley in his office at the ABC. When Butterley suggested a sound education in music theory was necessary before composition lessons, Ahern moved on to Richard Meale.

In 1966, just before his 19th birthday, Ahern completed his first orchestral work, After Mallarmé, which impressed Meale so much that he suggested John Hopkins record it. Hopkins did (though it was not performed publicly until 1969), and submitted the recording to the 1967 UNESCO International Paris Rostrum, where it was placed equal 32nd in the judging, above his former tutor-of-sorts Butterley. The composer who shared 32nd place? Elliott Carter.

Ahern’s meteoric rise didn’t stop there. Hopkins commissioned another orchestral work for the following year’s Proms, in response to which Ahern wrote Ned Kelly Music. Seen at the time as a comic piece (several members of the Sydney Symphony refused to fold paper aeroplanes and throw them around as part of the performance, and wouldn’t even utter the words ‘Ned Kelly’), Peter Sculthorpe later mused that it was probably misunderstood:

Ned Kelly Music was actually a very serious statement . . . a few of the reviews and certainly people in general just took it as an hilarious entertainment and I didn’t think that was David’s intention at all. I think he was using the figure of Ned Kelly as somebody standing against authority and making an important statement…(Sculthorpe 2007)

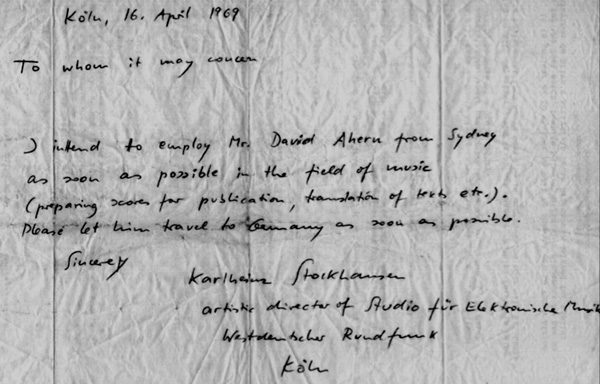

Now seeing himself as a vastly experienced and matured composer, Ahern felt that he had outgrown his teacher in Meale and looked to Europe for inspiration. He wrote directly to Karlheinz Stockhausen, and managed to worm his way into his 1968 Darmstadt course (despite the fact that it was already full), only to send messages later in the year with the news that he would be remaining in Europe to fill the role as Stockhausen’s compositional assistant.

Stockhausen’s primary focus at Darmstadt that year was his recently completed set of text-compositions, Aus den Sieben Tagen (written in seven days with little food or sleep in a meditative state after his second wife had left him), pieces which, if anything, prefaced the direction Ahern would adopt the following year in the text pieces members of the Scratch Orchestra wrote and performed. It was actually in late 1968 that Ahern first travelled to England and met Cardew, who ironically had been Stockhausen’s assistant 10 years before.

After a brief trip back to Australia in 1969 to replenish his funds, Ahern returned to Germany, performed for a short while with Group Stockhausen and then returned to London where he performed on the same stage as Skempton on the night that the Round House rats were mesmerised by La Monte Young. While he did work further with Stockhausen, his time with Cardew was most formative.

The relationship between the composer, performer and audience was not to be blurred, it was to be obliterated...Ahern was so inspired by Cardew’s approach to composition and music-making that he decided to return to Sydney to promote it himself. Cardew’s experimentalism was a practical one. While ‘Cagean’ in the wish to allow ‘sounds to be themselves’ and to disassociate the composer from the act of composition, Cardew developed very specific interpretations of these ideas about performance: the Scratch Orchestra was to be a performance group.

The relationship between the composer, performer and audience was not to be blurred, it was to be obliterated, and the first instance of this was the openness of the Scratch Orchestra to any person, whether or not they had had formal music training.

For Ahern, however, there was never any question of joining a specific camp. For all the importance that is today made of the differences between the experimental and serial composers, and as ‘Cardewian’ as his activities became, Ahern was only interested in what was new. The Scratch Orchestra, with its unique approaches to performance and the application of the experimental aesthetic that any sound, intended or not, is musical, simply opened up new avenues to the Australian.

Here was not a way of changing how one composed or how one played: Ahern learnt to change the way one listened. In many ways, this can be related, as much as Stockhausen might protest, to the ‘Seven Days’, and indeed that work was included in the list of compositions in the draft constitution of the Scratch Orchestra (Cardew 1969).

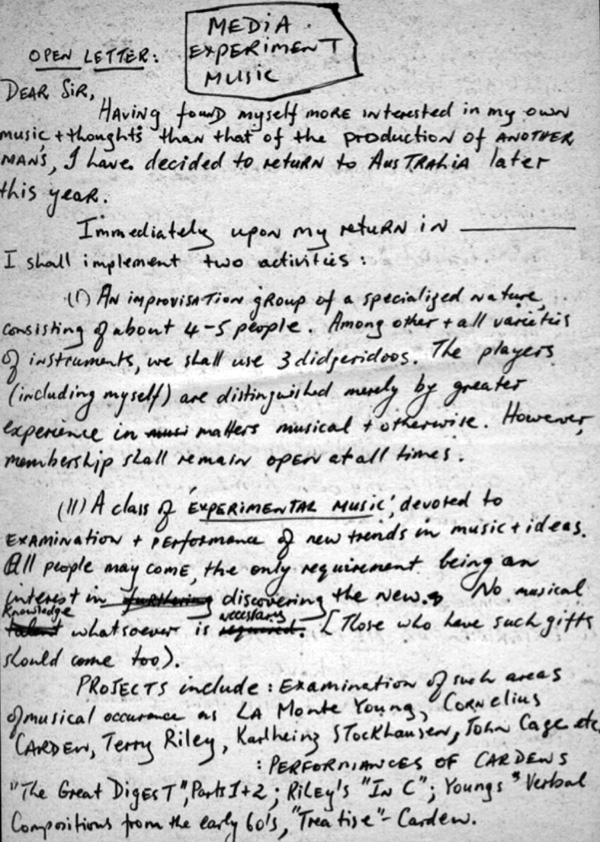

Back in Sydney, Ahern proposed that he should run a course in experimental music at the (then) NSW State Conservatorium, a request that was approved by the director, Joseph Post. Just 2 years after the premiere of Ned Kelly Music, Ahern was back to teach and to lead.

[David Ahern’s proposal letter, sent out on his return to Australia in 1969.]

From the very beginning of the course, Ahern had his own group of followers. Out of the courses he first conducted at the Conservatorium and later, through the WEA (Workers’ Educational Association), Ahern developed a number of performance and improvisation ensembles, although their mode of performance and choice of repertoire changed markedly over the following years (Geoffrey Barnard was the first to identify two clear divisions in the modes of performance group AZ Music, from an early Cardewian approach to a later one of more prepared and formal repertoire (Barnard 2000, pp. 45-46)).

From 1970 to 1972, performances by these groups were aligned closely to the Scratch Orchestra’s own approach, with Ahern’s variations and his slightly more eclectic influences. And influence others he did as well. While Ahern’s name is not a standard topic in Australian Music 101, we might well recognise the names of those who studied and performed with him during these years: Roger Frampton, Greg Schiemer and Geoffrey Collins, to name but three.

|

SCRATCH ORCHESTRA – JUNE 1969 Cornelius Cardew Arose from Cardew’s Morley College course and the Draft Constitution

Scratch Music Notes performable continuously for indefinite periods

Popular Classics Players join in as best they can

Improvisation Rites A community of feeling - also free improvisation

Research Project Travels in many dimensions

Compositions La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Cornelius Cardew, John Cage, Christian Wolff, Christopher Hobbs, etc

‘A Scratch Orchestra is a large number of enthusiasts pooling their resources (not primarily material resources) and assembling for action (music-making, performance, edification).’ - Cornelius Cardew |

AZ MUSIC – FEBRUARY 1970 David Ahern Arose from the Laboratory

Glees Glees are patterns and preparations for song

Singalongs Find and sing along with a classic

Improvisation Rites

Catalogues A catalogue is an ordered representation of what you hear and what you see

Compositions Similar repertoire

‘Many of the procedures that Cardew adopted for the Scratch Orchestra in its exploration of sound and of listening experiences were also adopted by ourselves. His Draft Constitution provided a strong basis for our own private performances and improvisations.’ - Ernie Gallagher |

Sadly, these were not heady days of success for Ahern in his home town. Australian audiences were less enthusiastic in reaction, to say the least, than their European counterparts. And many of Australia’s concert reviewers, whom one might have thought would have been well educated enough to understand the intent of the new music, were terribly negative: Fred Blanks at The Sydney Morning Herald and Frank Harris at The Daily Mirror revealing such ignorance as:

The lion’s share of Sunday’s program, presented by David Ahern and a small band of followers, was devoured by the one-hour long Concert for Piano and Ensemble by John Cage, venerable father-figure of the avant-garde. This scrambled compendium of noises, some born of musical instruments (not always by conventional birth) and others produced by all manner of means involving childish visual fun, is meant to pose the question: ‘What defines a valid ingredient of music?’. (Blanks 1970)

At a later date, Geoffrey Barnard recorded some of the more negative audience reactions, too:

At the Sydney Proms in February, an augmented AZ ensemble took part in a realisation of Paragraph 2 of Cardew’s The Great Learning, simultaneously with the first public improvisation of the group Teletopa...A good number [of the audience] were overtly aggressive, jostling performers, snatching drumsticks out of their hands or tipping water on them from the upstairs balconies. The Town Hall guards joined in the occasion, and one such charismatic individual...threatened to break me in two if I didn’t pack up my gear and clear out. (Barnard 1989, pp. 17-20)

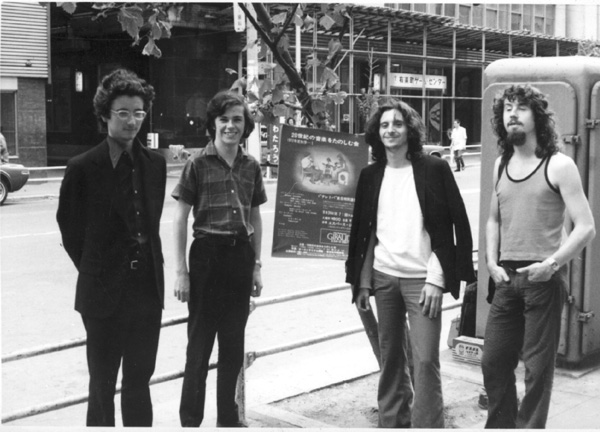

Reading correspondence from Cardew to Ahern over this period, one can glean that Ahern was understandably downcast at his reception in Australia. He decided to take his new improvisation group, Teletopa, on an international tour, to confirm that what they were doing really was relevant new music. Geoffrey Collins later reflected:

We started off by going to the Philippines cultural centre in Manilla… then we spent a fair bit of time in England at a large new music festival at the Round House, Chalk Farm, where we performed and got to hear lots of other improvisation groups… There was a concert on a train up to Edinburgh… and we went and spent time with Stockhausen and did radio broadcasts in Germany. We went to New York and spent time with Steve Reich and Cage and to Italy and Japan [with Toru Takemitsu] where we did a concert in a nightclub in Tokyo. He (David) was incredibly well connected and… within the space of a month I had met all the biggest names. They were very generous to David and us(Collins 2007).

The return to Australia had the same disastrous effects, however. Ahern’s reaction to the Australian public’s indifference to his music was to program concerts with set repertoire and professional performers, but he had already lost most of the zest with which he had first returned from Europe in 1969.

In November 1975, AZ Music performed its last concert (ironically promoting new Australian composers such as Robert Irving, Alan Holley and Robert Allworth), and Ahern was propping up much of his confidence and enthusiasm with the bottle. No further compositions have survived from this point to his death in 1988.

In one of its later concerts, on 16 November 1974, Ahern’s AZ Music performed Howard Skempton’s First Prelude, September Song and Waltz for Piano. This is the last living connection one can draw between the two composers.

David Ahern’s untimely demise surely contributes to the lack of knowledge young Australian composers have about his work in comparison to that which young English composers have of Skempton’s. And while his time active in Australia perhaps shone shorter and brighter than his peers’, there were many detractors to Ahern’s success, even in his early years as Hopkins’s and Meale’s favourite.

Is this Australia’s famed ‘Tall Poppy Syndrome’? Or is it just that Sydney society at the time wasn’t ready for what was new in Europe and the US? Surely with the kind of appreciation and respect Ahern commanded overseas, he was let down when he returned home? Perhaps a more English, refined, quiet and exacting Skempton-type would have been preferred in Australia too, one who might have enjoyed a 1990s renaissance when other new music began to tire audiences’ concentration.

These kinds of questions, while controversial, are quite pointless. Much more fruitful is the reflection that in the late 1960s, Australia produced another composer who turned heads all over the world and was capable of assimilating many current ideas into his own music-making. Ahern was not the only one – he was not even the only experimental composer in Australia in the 1970s, as any fan of Syd Clayton, Warren Burt and many others would testify.

But David Ahern’s music has not been studied in any great detail. His ideas have not been followed by a generation of younger composers in the same way that Howard Skempton’s have. The conclusions he drew and the aesthetic he refined for Australian culture lie like paths trodden only once. And since Ahern’s own trepidatious exploration of those paths was not entirely successful, they are already overgrown and some are possibly lost.

Now would be a good time for Australia’s young composers to go back and look for such overgrown paths. To find ideas such as Ahern’s that in other countries would have been explored many times over by now; to look for inspiration and education to elucidate their own compositional voices; and to bring that hidden and lost Australian music back to life: perform it, analyse it, teach it.

We know the immense value of Sculthorpe’s music. We know leading composers who have subsequently learnt and grown from it, like Matthew Hindson and Paul Stanhope, now treading new paths that we’re already (and rightly) busy scampering down. And Liza Lim. And Michael Smetanin. etc… But to the adventurous or even the tired: let’s look back, and wander down some of those other paths. Even if, at first glance, they may seem like dead ends.

References

Barnard, G. 1989, ‘AZ it was’. NMA, 7, pp. 17-20.

Barnard, G. 2000, ‘David Ahern: Starting from Scratch’. Sounds Australian, 55, pp. 44-46

Blanks, F. 1970, ‘Aural air pollution’. The Sydney Morning Herald, 7 July.

Cardew, C. 1969, ‘A Scratch Orchestra: draft constitution’. The Musical Times, June.

Collins, G. 2007, in interview with the author.

Sculthorpe, P. 2007, in interview with the author.

Further reading

Ahern, D. 1969, ‘Now Music’. Music Now, 1 (2), pp. 20-24.

Ahern, D. 1970, ‘Notes on expansion’, Other Voices, 1 (2), pp. 35.

Ahern, D. 1972, ‘Teletopian utopia’, The Bulletin, 6 May, pp. 49.

Ahern, D. 1972, ‘Teletopa’, Music Now, 2 (1), pp. 18-27.

Bryars, G. 1983, ‘‘Vexations’ and its Performers’, Contact, 26, pp. 12-20.

Cage, J. 1961, Silence. The Wesleyan University Press, Middletown.

Cage, J. 1968, A Year from Monday. Calder and Boyars Ltd, London.

Cage, J. & Barnard, G. 1980, Conversation without Feldman. Black Ram Books, Darlinghurst, NSW.

Cardew, C. 1972, Scratch Music. Latimer New Dimensions Limited, London.

Eley, R. 1974, ‘A History of the Scratch Orchestra’, in Cornelius Cardew (ed.), Stockhausen serves Imperialism. Latimer New Dimensions Limited, London.

Frampton, R. 1991-92, ‘ Teletopa, AZ Music, Free Kata and Free Improvised Music in Australia: an Autobiographical Perspective’, Sounds Australian, 32, pp. 21-25.

Gallagher, E. 1971, ‘The state of the art’, Music Maker, 38 (29), pp. 27-28.

Gallagher, E. 1989, ‘AZ Music’. NMA, 7, pp. 9-13.

Jenkins, J. 1988, 22 Contemporary Australian Composers. NMA Publications, Brunswick, Vic.

Kurtz, M. 1992, Stockhausen: A Biography, translated by Richard Toop. Faber and Faber, London.

Murdoch, J. 1972, Australia’s Contemporary Composers. The Macmillan Company of Australia Pty Ltd, Sydney.

Nyman, M. 1999, Experimental Music: Cage and beyond (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Prerauer, C. 1967, ‘Britten and Blake’. Nation, 21 October, pp. 21.

Ryan, P. 1994, ‘Cage on stage’. Art Monthly Australia, 68 (April), pp. 37.

Sculthorpe, P. 1999, Sun music: journeys and reflections from a composer’s life. Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Sydney.

Stockhausen, K. 1968, Aus den Sieben Tagen. Universal Edition, Vienna.

Scheimer, G. 1989, ‘Towards a living tradition’, NMA, 7, pp. 30-38.

Toop, R. 1982, ‘The Concert Hall Avant Garde: Where is it?’, Art Network, pp. 6.

© Australian Music Centre (2008) — Permission must be obtained from the AMC if you wish to reproduce this article either online or in print.

Subjects discussed by this article:

James Humberstone’s background is in community music and music education. He currently designs new music software and education initiatives for Sibelius as their Director of Application and Education and also works at MLC School in Sydney as one of three composers-in-residence in a composition-based music program. He is very active as a composer of both education and concert music for schools, colleges and ensembles all over Australia. James is currently a PhD candidate at UNSW, writing a case study on his primary school childrens’ opera which will be premiered in September 2008.

Comments

Add your thoughts to other users' discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

re David Ahern

by jenniferfowler on 12 March, 2008, 12:44am

My recollection of the years 1968 -9 in Europe was slightly at variance to some of the details in this article. For instance, I first heard about the Scratch Orchestra when I was living in Holland in Autumn 1968. There had certainly been some Scratch Orchestra events by then. Perhaps the formal formation with constitution etc took place in 1969, based on the earlier events?

I was at the Darmstadt Summer Course in 1968, and met David Ahern there. The chief Stockhausen event there was "In dem Haus", not Aus den Sieben Tagen - maybe Ahern was around during the later piece after the summer course was over? In dem Haus was an event where Stockhausen took over a whole house and set up different events in each room, linked by electronics. The idea was that the audience wandered around the house and could hear different things happening with sound leaking from one room to another. A number of assistants were managing the electronics, Ahern being one of them. Because of all the business of setting up the electronics, David missed all the other events at Darmstadt. I was glad I hadn't, as there were many fascinating master classes for performers specialising in contemporary music, as well as lots of other performances of Stockhausen's music.

Re David Ahern: Filling in gaps

by humbers on 19 March, 2008, 2:12pm

Dear Jennifer,

Thank you so much for the extra information you've provided. A lot of the information I collected was oral history, and in the thesis I wrote on which parts of this article are based I pointed out the weaknesses of such an approach (although it was wonderful to collect so many memories of David's work)!

I will take a note of your corrections about the Darmstadt course that year and also pass them on to Geoffrey Barnard, who is probably the greatest archiver of Ahern's achievements since inheriting his estate.

We will blame Cardew himself for any inaccuracies re the date of the beginning of the Scratch Orchestra: in Scratch Music (Latimer New Dimension, London, 1972) Cardew says "The Scratch Orchestra was formed on the basis of a Draft Constitution that I wrote in May 1969 ... The first meeting on July 1st 1969, was a gathering of about 50 people"...

Probably more accurate is Parsons' recollection that the Scratch Orchestra grew out of the course Cardew was teaching at Morley College. The events that you remember from 1968 may have been to do with those activities and the group formalised in 1969?

If you have any more detailed recollections I would love it if you would have time to email me directly. I really enjoyed the three years I spent gathering information about Ahern. The general biographical work I did I hope some day will be a jumping off point for someone to do some much more thorough research.

Best wishes,

James Humberstone

Stockhausen in Darmstadt

by Richard Toop on 26 June, 2014, 5:25pm

As Jennifer Fowler points out, the Stockhausen seminar project in 1968 was not to do with 'Aus den sieben Tagen'; it was a collective composition entitled (pace Jennifer) 'Musik für ein Haus' (Music for a House). By this time Stockhausen had certainly written the 'Aus den sieben Tagen' texts (in May), and Fred Ritzel's book on the seminar records comments by Stockhausen that certainly point in the direction of these text pieces, but they weren't specifically mentioned, let alone performed. Instead, they were the focus of his 1969 seminar, which consisted almost entirely of performances. For what it's worth, I was there (I had met Stockhausen for the first time just a couple of weeks earlier), and I attended not only all the seminars, but also all the recording sessions for Deutsche Grammophon in the Justus-Liebig-Haus.