18 December 2009

Martin Wesley-Smith's Who Killed Cock Robin?

a reflection by the composer

Image: Illustration from The Courtship, Marriage,&c. of Cock Robin and Jenny Wren

Image: Illustration from The Courtship, Marriage,&c. of Cock Robin and Jenny Wren © www.gutenberg.org

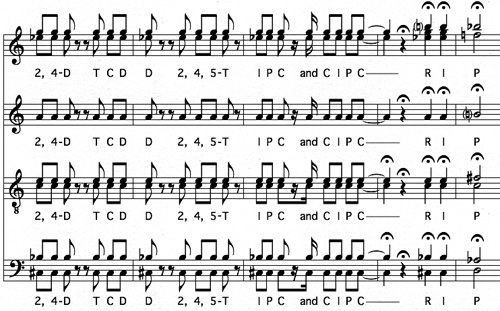

Who Killed Cock Robin? for a cappella choir (1979)

Music by Martin Wesley-Smith

Text by Martin and Peter Wesley-Smith

When I first read, aged 17, Rachel Carson's book Silent Spring, I was naive enough to believe that the world would heed her urgent warnings and act immediately to stop poisoning our environment. It didn't, of course. When, nearly twenty years later, I started researching an idea for a choral piece based on an English folk-song I'd enjoyed as a kid, I was shocked to find that the situation had deteriorated far beyond anything Carson had described. It became clear that the sparrow's bow and arrow were, in reality, a chemical that an uncle of mine, Brian Wesley-Smith, had campaigned against for years: 1, 1, 1-trichloro-2, 2-di (four chlorophenyl) ethane, commonly known as DDT.

Although most uses of DDT had been banned in the US in 1972, a total ban in Australia was not implemented until 1987. I composed my piece in 1979, hoping it might help draw attention to a chemical that was toxic not only to malarial mosquitoes but also to humans (it is suspected of causing cancer), fish, crayfish, cats... and birds, including the bald eagle, brown pelican, peregrine falcon and osprey (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DDT).

When I was a student I used to sing a lot. I was never very good at it, and had never had a '...singing is not only a great tonic but a great way to learn about music.'lesson, but I enjoyed it and believed then, and believe even more strongly now, that singing is not only a great tonic but a great way to learn about music. I sang in choirs and, at various times, in a folk group, in madrigal groups, in a male jazz quartet, and in a barbershop quartet. I wrote and arranged music for some of these groups, including Two Shakespearean Songs (1967), an a cappella choral piece still occasionally performed today. But I was also fascinated by electronic music, coming to grips in 1969 with a Moog synthesiser at the University of Adelaide. When I went off to study overseas, it was difficult to find opportunities to participate in vocal groups, so singing - except what I did with my kids as they were growing up - took a back seat.

In 1975, back in Australia, I became an activist on behalf of the people of East Timor and their right to self-determination, a right supposedly guaranteed by the United Nations but in practice ignored by the governments of, amongst others, America, Australia, Great Britain and Indonesia. In 1978, I put my activities as activist and composer together, composing an audiovisual piece Kdadalak (For the Children of Timor), designed to bring attention to appalling atrocities being committed against a people who had supported Australia, at great cost, during World War II. I was now an activist composer, ready to take on those who disparaged environmentalists and others as 'closet Marxists' or 'reds under the bed'.

In order for Who Killed Cock Robin? to make its political point, it had to be 'audience-friendly'. Thus I tried to write something that was, in some sense, 'entertaining' 'In order for Who Killed Cock Robin? to make its political point, it had to be "audience-friendly"'.(compelling, intriguing, whatever). It needed, I thought, some light-hearted songs to relieve the earnestness of the enquiry leading to the post-mortem report. I knew that this was courting danger - that henceforth I was unlikely to be regarded, by some, as a 'serious composer'. I also knew that it would help the piece make contact with its audience and thus help it make its point: the need to discuss banning the use of DDT and other dangerous chemicals. In all this, I was the idealised audience member: if I was somehow 'entertained' by the piece then there was at least a chance that some other people would be, too.

'Serious composers' back then were expected to write austere atonal music that was as difficult to listen to as it was for amateur choirs to sing. I remember going to one particular choral concert that featured a new piece and coming away wondering what the point of it all was: it wasn't a bad piece, in my view, but the choir hated it and the audience hated it; not surprisingly, the composer hated it too - not the piece, perhaps, but the whole experience. Yet it had all cost an enormous amount of money in grants for composition and performance. I vowed not to contribute to such a waste of effort and resources.

Let me say here that I have no problem with anyone writing whatever they feel they must. In fact I insist they do, for if music doesn't come from an inner compulsion then it's probably not worth much. But there's a time and a place for everything: generally speaking, hard-core new music should be performed in hard-core new music concerts at a university, say. Concerts for a general audience are the place for more 'audience-friendly' pieces. This is contentious, I know, and there will always be arguments about what is 'audience-friendly' and what is not. But concert entrepreneurs have to put on successful concerts while, we hope, exposing their audiences to interesting new music. They walk a fine line: too much difficult stuff, or too much pap, and they will lose their audience, which ain't good for anyone.

By 1979 I'd had lots of different musical experiences and had developed eclectic tastes and interests: I'd played banjo in a Dixieland band, and in a symphony orchestra playing works by Weill and Eisler; I'd played analog synthesiser in a symphony orchestra performing Stockhausen; my folk group had sung on Brian Henderson's Bandstand as well as on numerous other television shows, and we'd sung in coffee lounges and clubs, including the notorious Motor Club in George Street in Sydney, considered at that time to be the roughest club in Australia (that experience taught me a thing or two about getting across to an audience); I regularly wrote children's songs for my kids, and for Here's Humphrey and Playschool; I'd analysed Webern and played in an orchestra under Peter Maxwell Davies as well as in free-form improvisation groups; I once played reel-to-reel tape recorder in an ensemble conducted by Luciano Berio (for his Differences); and I taught electronic music composition, created music from tape recorders, designed musical installations, and was exploring audiovisual composition.

I enjoyed it all (well, not the Motor Club so much), and was not about to be told that 'serious' choral music had to be this or couldn't be that, even though the pressure to conform to some atonal ideal was intense. I resisted that pressure, and the songs went in. The piece was performed (by what was then the Sydney University Chamber Choir, conducted by Nicholas Routley), the choir enjoyed it, most people in the audience seemed to, it made its point about pesticides, and it was recorded and broadcast. It has since been performed many times by many different choirs.

It was gratifying when, years later, a prominent Australian composer wrote to me saying that Who Killed Cock Robin? gave him the courage to follow his own star and to resist the strictures of the contemporary music thought police. How absurd that composers should be so browbeaten! I detest any pressure to conform to someone else's ideal, particularly when it's applied to artists, and I believe that such pressure has stymied the development of much Australian music of the past forty years or so.

Remember the 'style wars' in the Australian Music Centre's Sounds Australian 'I've often tried to put two opposite emotions together in a piece, sometimes simultaneously...'journal during the 1980s? If you didn't write like Ferneyhough then you were not to be taken seriously. Composers writing works that were well-received by audiences were branded as 'whores'. It was all so childish, and damaging - yet some of it still remains, killing off diversity and helping to maintain so-called 'serious' contemporary music's irrelevancy to mainstream audiences.

Any performance of Who Killed Cock Robin? should exaggerate its extremes: light-heartedness and humour on one side, on the other the unbridled horror of the list of chemicals found in Cock Robin's body tissues. I've often tried to put two opposite emotions together in a piece, sometimes simultaneously, so that an audience member finds herself struck by the beauty of an image, say, but then suddenly realises that it represents or portrays something terrible. A massacre, for example. In Cock Robin, the humour, perhaps reinforced at times by theatrical presentation (costumes etc.), somehow enhances the seriousness, making it more chilling. Similarly, mixing idioms - or, say, tonal and atonal music - within the same piece can enhance the effectiveness of each. In Quito I tried combining passages from Lassus (his Timor et Tremor) with a pop song written by a young Timorese man who suffered from schizophrenia, finding that each became more interesting and beautiful when heard in a different context.

In recent years I've been singing in a choir again - a fascinating as well as useful experience. I started in Carlos Alvarado's Courthouse Choir in Berry, then joined a seven-voice vocal group - The Thirsty Night Singers - in Kangaroo Valley. Being a composer myself, and a pedant, I must admit that I'm easily irritated by other composers' works - by sloppy notation, say, or passages that seem to me to be unnecessarily difficult. But I'm also learning a lot from singing, and sometimes conducting, new works, especially new works by Australian composers - learning to push myself out of my comfort zone, for example, as composer and performer.

The Thirsties sing - or try to - a Gene Puerling arrangement of A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square (the version recorded by Manhattan Transfer). When I first looked at it, I thought some of the chord sequences distinctly odd. But when we sing them perfectly (not easy), they sound magnificent. Exhilarating! Puerling breaks every rule in the book, doing things I would never have done, like putting the tenor part in one important chord one semitone above the melody being sung by the sopranos. Never too old to learn, I'm now encouraged, belatedly, not to shy away from such things when composing and arranging for voices. In fact, looking back at Who Killed Cock Robin?, I would love to have another go at some of the different four-part arrangements of the main melody ('All the birds of the air fell a-sighin' and a-sobbin'). While I'm resisting that temptation, I recognise that my choral writing improves in some way - is more practical, sits better - when I'm actively involved in choral music.

I've mostly tried to create music that comes from the experience of practical music-making. At one time, I would use a piano to experiment with ideas. When composing a song, I would sometimes use a guitar. Playing, literally, with control voltages in an analog synthesiser would lead to sounds and sequences I could not possibly have imagined. When I first got my hands on a computer that could play sounds, I created music based on random numbers, and marvelled at some of the sequences that were created. I experimented with acoustic representation of external data (e.g. I made melodies from strings of nucleotides in DNA molecules), and I played nursery rhymes backwards and upside down, Lewis Carroll-style, to hear what resulted. Some of those melodies appeared in my choral piece Songs for Snark-Hunters (1985), and in my full-length choral music theatre piece Boojum! (1986). All these techniques have been useful, some of them particularly so when composing choral music. I've been fortunate, too, in having had numerous performances by some excellent ensembles, including the Sydney Chamber Choir, the Sydney Philharmonia Motet Choir, and The Song Company. Sitting in at rehearsals, trying to sing each part myself, and listening, listening, listening, have taught me far more than I ever learnt - or could teach - at music school.

When asked how to write for children, author Barbara Kerr Wilson (ex-wife of the late lamented Peter Tahourdin, my first composition teacher) said something like 'Write for yourself and hope that children like it'. Since Cock Robin I've composed for myself in the hope that at least some other people will like it. If they do, lovely; if they don't, well, too bad. At least Mum will. Can't win 'em all ...

Further links

Martin Wesley-Smith - AMC (www.australianmusiccentre.com.au/artist/wesley-smith-martin)

Martin Wesley-Smith - homepage (www.shoalhaven.net.au/~mwsmith)

Who Killed Cock Robin?- resources on MW-S's homepage

(www.shoalhaven.net.au/~mwsmith/cockrobin.html)

DDT - Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DDT)

Rachel Carson: Silent Spring - Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silent_Spring)

Boojum! - resources on MW-S's homepage (www.shoalhaven.net.au/~mwsmith/boojum!.html)

Quito - resources on MW-S's homepage (www.shoalhaven.net.au/~mwsmith/quito.html)

The Song Company (www.songcompany.com.au)

The Sydney Chamber Choir

(http://www.sydneychamberchoir.org/)

Who Killed Cock Robin? was recorded by the Sydney University Chamber Choir, conducted by Nicholas Routley, and release on EMI LP OASD.7629, now out of print. It was subsequently recorded by an expanded Song Company on The Green CD (Tall Poppies TP064).

© Australian Music Centre (2009) — Permission must be obtained from the AMC if you wish to reproduce this article either online or in print.

Subjects discussed by this article:

Adelaide-born composer Martin Wesley-Smith established the Electronic Music Studio at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, teaching there for 26 years till he resigned in 2000. He now lives in Kangaroo Valley, New South Wales, where he composes, puts on fund-raising concerts, grows vegetables and keeps chooks.

Comments

Be the first to share add your thoughts and opinions in response to this article.

You must login to post a comment.