7 May 2025

Remembering Nigel

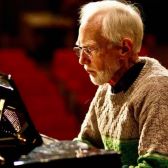

Image: Nigel Butterley performing ‘Sonatas and Interludes’ by John Cage, in Bundanoon.

Image: Nigel Butterley performing ‘Sonatas and Interludes’ by John Cage, in Bundanoon. © Unknown photographer, photo supplied by Tom Kennedy.

On May 13 this year, the composer Nigel Butterley (1935-2022) would have turned 90. Whatever you personally believe about what happens after life - we enter nature, we endure through love and the acts of love we've done on earth, or we pass through to some kind of spiritual 'beyond' - Nigel Butterley's artistic world gives voice to those deepest convictions about the big questions of being. His vision was vast, and it was as caring as it was careful, just as he was.

Having already written my own, partial and personal, introductory guide to Nigel's music for Nigel's 80th birthday, I decided to do something a little different this time. I have invited a number of performers and composers who have had relationships with Nigel's music or Nigel himself, to offer their thoughts, selecting particular pieces or memories to mark the occasion.

Composer and broadcaster Stephen

Adams, still remembers hearing Nigel's music for the first

time, on an LP - possibly at the AMC itself. Of

Meditations of Thomas Traherne (1968), written by Nigel

upon receiving the

Albert Maggs Award, Stephen said:

"…Hearing it for the first time was such an incredible

ecstatic experience!

I remember being enthralled by the richness of the musical

colours of the piece, and its sense of shifting eddies and surges

of darkness and light. The light most strikingly evoked by those

sudden bursts of a children's recorder chorus.

… how wonderfully strange and fresh that sound world felt

bursting into the orchestral sound world, very much as if a door

had suddenly opened in the heavens, letting in a sudden powerful

shift of light.

Meditations is a piece I still love, and have fond memories

also of playing it to my children 30 years later and seeing them

experience a similar sense of wonder on hearing it."

About the starkly contrasting Explorations (1970),

"perhaps Butterley's boldest and most confronting achievement"

(Gyger 2015, p.87), fellow composer and broadcaster, Andrew Ford, has a similarly

enduring recollection:

"I find there's often something compelling about Nigel's

music, something (it's hard to say what) that grabs my attention

and won't let go. The first time I experienced this phenomenon

would have been 40 years ago, shortly after I arrived in

Australia. I was driving in Sydney when Explorations came on the

radio. I missed the introductory announcement but was immediately

grabbed by the music. Reaching my destination, I sat in the car

on a suburban street until it was over and I learnt what it was.

It's a vivid memory."

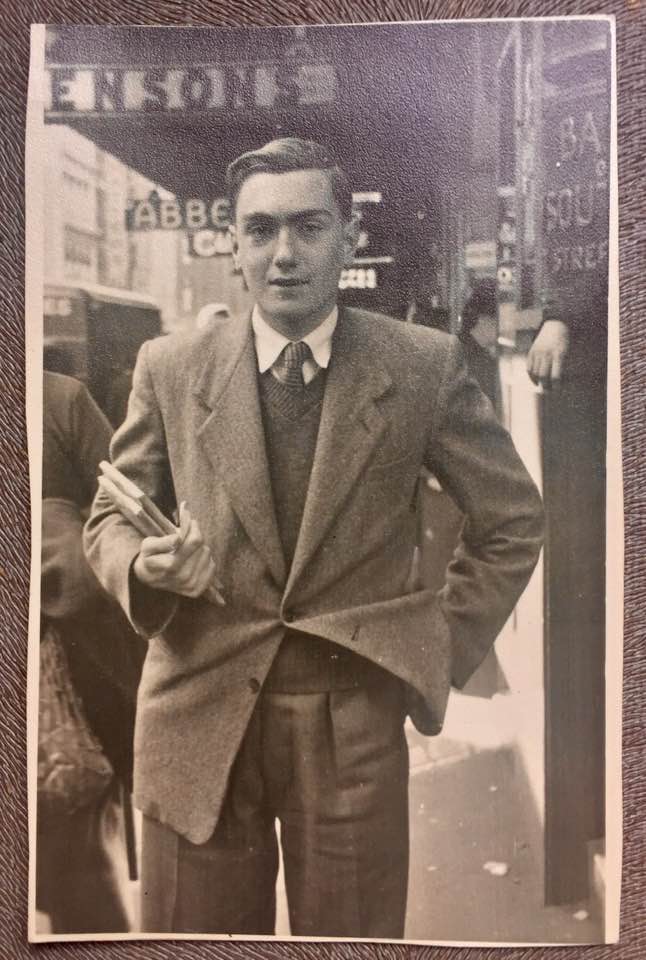

[Photo by Tom Kennedy of a photo by Noreen Butterley]

Performer, artistic director, and educator, Jenny Duck-Chong says that Nigel was a

"musician's musician" who possessed a "deft understated command

of his forces in every work" she experienced, a music "full of

subtle nuances, shades and timbres", that showed "a deep

appreciation of the voice and its ability to shape music with

both colour and meaning."

Amidst many years of involvement with Nigel's music - including

Halcyon's

commissioning what would become Nigel's final completed work

Nature Changes at the Speed of Life (2014) - Duck-Chong

remembers Orphei

Mysteria (2008), another Halcyon commission, as "utterly

beautiful, austere and mellifluous":

"... Even now I can vividly hear certain sections of the

piece, where he drew together the sonorities of voice and

ensemble so expressively, evoking the drama of the

text."

The work was, however, not without technical challenges:

"…Thankfully we had been singing together for almost two

decades at this point and knew each other so well we could pull

this off (even as we exited to either side of the stage in the

epilogue with our backs to each other). This ritualistic exit, as

we departed into stillness, was, as so much of Nigel's music,

captivating in its unassuming simplicity. But there was nothing

simple in its inspiration or execution. It was finely wrought

craft."

Two other exceptional performers, Stephanie McCallum and Zubin

Kanga, single out Nigel's solo piano piece Uttering Joyous

Leaves - one of many pieces Nigel dedicated to his partner

Tom - for special mention:

"I have a great affection for Nigel's piano

piece, Uttering Joyous Leaves (1981), and feel it was one of the

best ones to emerge from the Sydney Piano competition commissions

over the decades. I included it in a very well-received recital

in Wigmore Hall as a London premiere in, I think, 1986 before

moving back to Australia. I have also had many students enjoy

learning it for student recitals. The piece remains unique in

quality of texture, rhythmic structure and upward floating

intensity, and the prefatory poetic reference is

inspirational." - Stephanie McCallum

"A career highlight for me was performing as part of Nigel

Butterley's 80th Birthday Concert in 2015. The concert featured a

new piano concerto by Elliott Gyger, From Joyous Leaves,

which I performed with Arcko Symphonic Ensemble and conductor Tim

Phillips. The concerto featured many different references and

tributes to Nigel, including the gradual introduction of prepared

piano sounds (referencing Nigel's Australian premiere

performances of John Cage's Sonatas and Interludes) as

well as musical references to his solo piano work, Uttering

Joyous Leaves.

I also performed Nigel's Uttering Joyous Leaves at

this concert, and this was such an extraordinary piece to perform

and interpret. Full of contrasting colours, from effervescent

passagework, to sparkling crystalline chords, to dark, skipping

basslines, the work was a joy to play. It's a high point of the

Australian piano repertoire, and a work I continue to recommend

to pianists." - Zubin

Kanga

Timothy

Phillips described the same concert as one of his "proudest

moments as a musician":

"… a spectacular concert that featured In the Head the

Fire, a new commission of Elliott Gyger's: From Joyous

Leaves and Nigel's monumental From Sorrowing Earth.

Already in the early stages of Alzheimers Nigel was perplexed

when taking his bow that the orchestra was playing happy

birthday to him. I wish his music could be heard more frequently

and by a wider audience as Nigel, a true gentleman, was one of

our most original and unique voices."

Timothy developed "a deep appreciation" for Nigel's music over

the years and was also "proud to say a deep and mutually

respectful friendship" with Nigel and his partner Tom. When

returning to Australia in the early 2000s, "possessed by a vision

that Australians should be performing and programming Australian

classical music", Phillips said Nigel's music was high on his

list and the group he founded, Arcko

Symphonic Ensemble, includes a number of additional works of

Nigel's amongst their repertoire:

The Canticle of David,

Laudes,

Forest I

and II , and

Three Whitman Songs.

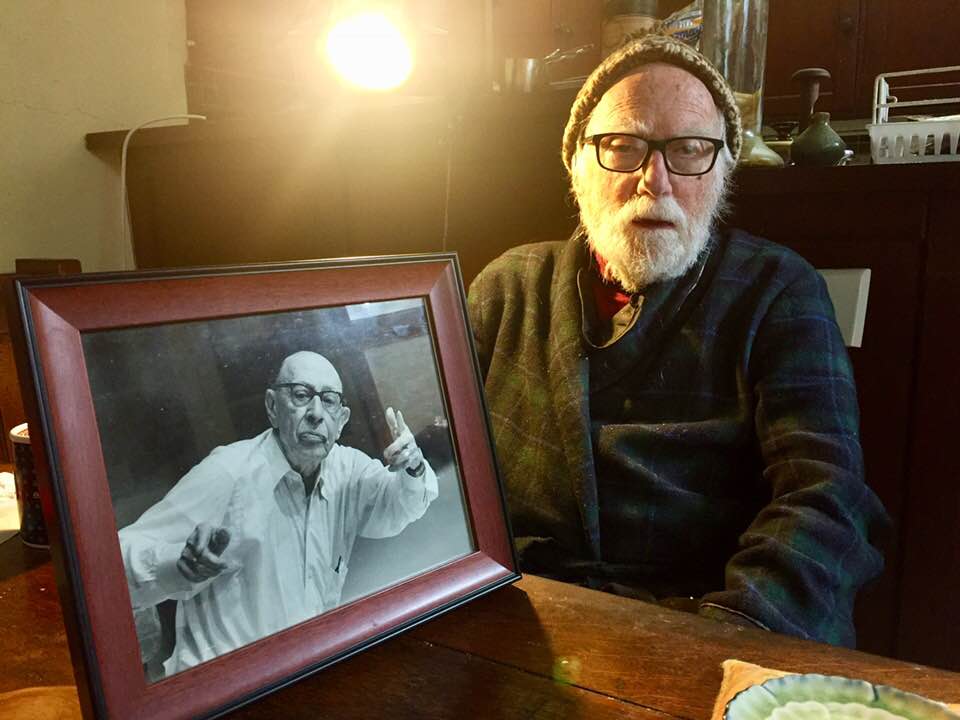

[Photo by Tom Kennedy]

Conductor Bryan Griffiths

notes how audiences respond to his programming and championing of

one of Nigel's lesser known works, Pentad (1968):

"Since completing a critical edition of Pentad in

2017, it has always been received with warmth and fascination

wherever I've directed the work in performance, even-or perhaps

because-its modernist abstractions challenge received ideas of

what the wind band can be."

Griffiths still recalls "the first thrill" of discovering the

manuscript of Pentad on the shelves of the Sydney

Conservatorium library, "an autographed masterpiece of modernist

music for wind and brass shelved humbly among the general

catalogue, composed by one of our greatest."

Written in 1968, the same year as Meditations of Thomas

Traherne, Elliott Gyger describes the music of

Pentad as "bold, abstract and ritualistic, as far

removed as possible from Meditations of Thomas

Traherne's numinous mystery" (Gyger 2015, p.97).

Elliott Gyger's book on Nigel's music (Gyger 2015) is an

invaluable resource, balancing rigorous analysis with contextual

and poetic insight. Reflecting, a decade after its publication,

Elliot had this to say:

"Writing about Butterley's music has brought me into close

contact with pretty much everything he wrote, but the pieces

which I know most deeply are unsurprisingly those which I have

performed, as a choral singer. With Sydney group the Contemporary

Singers, I sang Flower in the crannied wall - a luminous

short motet, with plainchant-derived diatonic clusters supporting

an elegant melodic line passed from voice to voice - and the

virtuosic Emily Dickinson cycle There Came a Wind Like a

Bugle, written for the Song Company. These two pieces taught

me an enormous amount about composing for unaccompanied voices;

at the time there was little if anything in the Australian choral

repertoire to match their level of textural invention. They are

also beautiful, succinct and flexible responses to striking

poetry, with an unerring sense for apt word-setting, and

interestingly almost no text repetition.

Similar qualities were to reappear a few years later, on a

much grander scale, in the wonderful choral-orchestral Spell

of Creation - a work which I can claim to know in more detail

than any other Butterley work simply by virtue of having typeset

it, and preparing the parts and piano reduction for the

premiere. Spell of Creation tackles profound themes of

faith and doubt: the former via mystical religious texts from

diverse traditions, and the latter in the poetry of Kathleen

Raine, which was so central to Butterley's later music. The score

encompasses extremes of complexity and transparency, including

ecstatic Hildegard settings tossed back and forth between

antiphonal choirs of voices and brass, orchestral textures of

shimmering beauty under deeply moving solos for soprano and

baritone, and an ending of riddling mystery. Singing in the

premiere performance in 2001 was an incredibly rewarding

experience, hearing the masterly imagination of every moment

contribute to a compelling overall vision. Described by Sydney

Morning Herald critic Peter McCallum as 'possibly the most

important choral work yet written in this country', Spell of

Creation has yet to receive a second performance."

I'm particularly pleased to have invited others to share their

thoughts for this article because it not only created a

reflection of the music that I simply could not have made alone,

but the process also reminded me of the unique pleasure of

mentioning Nigel to those who knew him or knew of him. You

immediately feel the generosity Nigel put into the world,

returned.

Nigel's close friend, the composer and teacher

Robert Smallwood sums this up perfectly:

"Even so many years later I still recall the pleasure of

meeting Nigel for the first time. The surprise was that such

wonderfully assured writing came from someone so genuinely

modest. I did not imagine then that our meeting would lead to a

lifelong friendship of more than 40 years.

…I last saw Nigel in January 2022 in a nursing home in

Stanmore, not far from his home. Dementia had taken his memory

from him. Although he could not remember me, he enjoyed telling

the staff that I was his lifelong friend. His musical memory was

still powerful, as he sang and recalled Rachmaninoff

preludes.

…Nigel's music favours intricate, even elusive gestures. It

invites listeners to join, examine and penetrate. It does not

present its ideas overtly or simply. The listener is rewarded

upon repeated listening as its depth and layers unfold and reveal

themselves."

Those revelations continue, and endure.

[Photo by Tom Kennedy]

References

Gyger, E. (2015). The Music of Nigel Butterley. Melbourne:

Wildbird Music.

© Australian Music Centre (2025) — Permission must be obtained from the AMC if you wish to reproduce this article either online or in print.

Subjects discussed by this article:

- Nigel Butterley

- Robert Smallwood (Interviewee)

- Timothy Phillips (Interviewee)

- Bryan Griffiths (Interviewee)

- Stephen Adams (Interviewee)

- Andrew Ford (Interviewee)

- Jenny Duck-Chong (Interviewee)

- Stephanie McCallum (Interviewee)

- Zubin Kanga (Interviewee)

- Butterley, Nigel

Composer Chris Williams was mentored by Nigel Butterley for a number of years and also worked as his musical assistant. He is currently pursuing doctoral studies in the United States of America as a composition candidate at Duke University. His music has been performed by the Flinders Quartet, The Song Company, the Tasmanian and Melbourne Symphony Orchestras, amongst others, and has been heard at Carnegie Hall.

Comments

Be the first to share add your thoughts and opinions in response to this article.

You must login to post a comment.