19 June 2018

As a composer

Image: Mark Isaacs

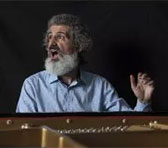

Image: Mark Isaacs © Louie Douvis

This article by composer and pianist Mark Isaacs, turning sixty this week, underlines the importance of teachers all through the artist's career - but perhaps most importantly during those formative years when a 'bumptious prig' received the encouragement and guidance he needed to find his way. This article was first published on the Loudmouth e-zine of the Music Trust and is reproduced here with permission. After his birthday concert in Sydney on 21 June, you can again catch Mark Isaacs and his piano solo extemporisations at Bird's Basement in Melbourne on 12 July.

The calling to be a 'classical' composer was instilled in me at the start of high school. Thanks to extraordinary teachers and mentors throughout those school years, I have stuck with my journey along that path through to this day, as I will to my last. Being a composer is my core identity, my musical ground zero.

I'd had piano lessons from age five, and, by age nine, began to make up things at the piano. I could already then play by ear most music I heard around me in my own busked-out, ham-fisted, yet fully-harmonised, way, but now I also started to venture into bringing forth my own little tunes. Sometimes my younger brother Steven would come and sing along with me, inventing lyrics to suit. I remember the words he put to one of my melodies betrayed an agenda of his own, as they began 'Please, stop your work and play with me'. I suppose I am still rather assiduous.

My musical days at Carlton South Primary School in Sydney involved playing in the recorder band and singing quite difficult repertoire in multi-part harmony in the school choir, with a very skilled visiting accompanying pianist and coach in Audrey Oertel. The school made an in-house LP vinyl record of the choir, and it was all tremendous, beautiful fun. We did a scaled-down Bach cantata, too.

I remember Miss Meades, the teacher in charge of music, suddenly walking into the empty school hall while I was a busy ten-year-old making up some music at the piano. I shrunk and stopped abruptly upon seeing her, but she urged me to go on. I refused. It seemed too private a thing, then, this composing lark, almost shameful. I was Dux of my primary school but needed a real mentor to find true direction.

That role was first filled by Christopher Leechman, the redoubtable music teacher during my years (1970-75) at Sydney Technical High School, a state boys' school in the Sydney suburb of Bexley (we lived in Kogarah; both were quite solidly working-class areas).

Leechman, who hailed from England and had studied at the Sydney Conservatorium with the great Russian piano master Alexander Sverjensky, was extraordinarily charismatic - rather like the Robin Williams character in Dead Poets Society - and we, 'the music kids', were his willing acolytes. He would organise music weekends on hired Halvorsen boats that cruised the Hawkesbury River, or would seize on a bunch of us, suddenly taking us out of school in the middle of the day for an activity he considered more important than the assigned lessons, such as traipsing into the city to watch the 1970 movie version of Alexander Solzhenitsyn's One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (its dark score by Norwegian composer Arne Nordheim gripped me as much as the story's gruelling realisation on screen). Along the way he'd decide we needed to taste unheard of things found then only in delicatessens, like camembert cheese, rollmops and English pork pies. His beaten-up car was almost knee-deep in books.

Leechman wrote two original operas for the school during my time there, for which I was expected to work out my own piano continuos by ear and help him with some of the instrumental arranging. Libretti were by Barry Donlon, our Oxford don of a librarian. Slattery's Band was the title of the first one, and I still recall fondly the irreverent wit with which the librettist's program note for the work ended: 'Slattery's Band is no Parsifal, but then again, neither is Parsifal'.

I spent every recess and lunch time of my six high school years in Room 3, the music room, hanging out with Leechman and the rest of the music gang, all of us attuned to our mentor's every utterance while he chain-smoked cigarettes and drank mugs of instant coffee as black and strong as tar, with five sugars. Other distinguished Australian music-makers who emerged from our ranks were harpsichord-builder Carey Beebe, opera singer John Davies and mandolinist Stephen Lalor.

Leechman was a great generalist too. He would take on the entire school in the mandatory music classes in Form 1 (now Year 7), striding over to the turntable affixed to the wall in order to disk jockey Elgar's Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1 as a kind of call to arms. Next would come something ravishingly melodic like Smetana's The Moldau and then it was on to the big guns: Sibelius, always Sibelius. The finale of his 5th symphony that he would invariably play remains, in my view, a singularly accessible masterpiece for those new to classical music (I've tested it to good effect on my daughter's boyfriends).

Amongst his favourite works, Leechman also gave pride of place to Vaughan Williams's Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis, and I still remember how struck I was when he confided in me that his most fervent wish would be to conduct this deeply mystical work at night in a forest. Already I was beginning to sense that life should be about these kinds of wildly passionate experiential aspirations of the spirit, facing off the naysayers who might pollute souls with their raw and profane, materialistic values. Later Jim (Jock) Black, another giant of a schoolteacher, would relentlessly draw out those kinds of themes from our studies with him of English literature in the senior high school years.

It might be mentioned that Leechman repeatedly dubbed me a 'bumptious prig'. I was too much of a bumptious prig to look up those words in the dictionary, being content to bask in the backhanded compliment I imputed to myself of inspiring such grand-sounding appellations from the master. Irritating him by pointing out occasional infelicities in his blackboard harmonisations, and looking transparently bored when he espoused to the class information that to me was rudimentary, one day - when I was still twelve - he angrily barked at me to compose something right there at my desk by end of class, since I was clearly not going to engage productively otherwise. I'd never really written down any of my inventions before, but, having become familiar with the baroque suite form, I duly took up a pencil and composed a Sarabande on my music pad. Leechman liked it, he really liked it. Eyes shining, he said 'You are to be a composer', and I immediately obeyed, and still do.

I quickly wrote an Allemande, a Minuet and a Gigue to go with my Sarabande, and arranged the suite for woodwind quartet. It was played at Speech Night, the first public performance of a written work of mine, at age thirteen, cementing in me for life the primacy of the idea of sitting in the audience - not on stage - while one's music was played.

But I was in a hurry. Having been force-fed Sibelius symphonies along with the camembert, I had quickly decided that I really wanted to be was a symphonist, an aspiration which Leechman firmly encouraged. I lay in bed each night from age thirteen with orchestration books - Forsyth, Lovelock, Rimsky-Korsakov - and slowly taught myself to orchestrate. Of course I was then light years away from writing a symphony, but by age fourteen I nonetheless produced the score of a short work for piano and orchestra, and then, by fifteen, a second little 'piano concerto', written at a table as I scribed away for the most part of what was a family holiday.

Recognition came. I was too young - as all are - to receive the lavish attention afforded to a 'child prodigy'. There was a sense of unlimited promise - newspaper articles appeared declaring that I was some kind of budding genius - and it was as if by age twenty-five I should expect to be basking in a flooding international recognition that I still haven't enjoyed at age sixty. That potential deep disappointment of unfulfilled promise when such artificially ebullient formative days are left behind can imperil the muse and embitter the soul, but I have chosen to remain always the eternal novice and never change my course. My teachers hover over me and firmly forbid it!

But early recognition creates its own forward motion. By age fourteen I had won two national composing competitions with my first little piano-concerto-type-thing. There was the 1972 Second National Series of Competitions for Musical Composition by Students organised by the University of Western Australia, which I won in my under-fifteen age category. The adjudicator was the towering Australian composer Don Banks, and, remarkably, I was sent a one-page report from him on my work. It was a nurturing and encouraging screed while yet exhorting me firmly to go much further. I still have the document, as I do the full list of prize-winners. For some reason back then, in early 1973, I was fixated on a name in the age category above mine, an entrant who had received a 'Commended' award. It was a name then completely unknown to me and everyone else, yet 'Carl Vine' in print seemed to have an energy about it, such that I kept staring at it. Who understands this kind of strange prescience?

At fourteen I also shared first place in the 1972 Frank Hutchens Scholarship for Musical Composition open to composers under the age of twenty-five (a co-winner was composer Brian Howard, then 21, much later to become one of my many composition teachers). This award produced a stipend to be used to study composition privately, and I can still see my mother at our red rotary-dial telephone, speaking to the Sydney Conservatorium (while I hovered eagerly) asking for a composition teacher for me. 'We don't have a composition teacher', they told her, 'but we can give you Vincent Plush'. Vincent was then a lecturer in his early twenties, and would go on to become one of Australia's more distinguished composers, and now also a classical music critic for The Australian.

So, as an eager young junior high schoolboy I trotted along to the Conservatorium, or otherwise Vincent's apartment, where he cooked up concoctions he described as his 'solution', and found new wonders in store for me. Amongst a banquet of many dishes, Vincent served me Stockhausen's Kontakte, the organ music of Messiaen (which I especially liked) and saw that I had a fairly thorough grounding in serial twelve-tone techniques. My music was nothing like that, but Vincent knew that I was eager to learn, and was very supportive of me performing my first romantic little piano-concerto-type-thing on national prime-time television with a symphony orchestra conducted by the television tycoon Hector Crawford.

I won the Frank Hutchens scholarship for a second time at age fifteen and was duly assigned avant-garde composer (and later peak media executive) Kim Williams as my composition teacher. Kim had me pore over his copy of Bach's Two-Part Inventions which he had meticulously marked up to elucidate their internal motivic consistencies. It's still the copy I use, which he has happily bequeathed me.

Meantime, I was again blessed that the local suburban piano teacher my parents had found, Heather Silcock, was also a most formidable musician as well as an AMEB examiner. She had been a protégée of the great composer and pedagogue Dr William Lovelock - whose orchestration book had been one of my bibles - and Mrs Silcock took me right through a thorough grounding in harmony, counterpoint, fugue and orchestration using his materials, these theoretical studies being an adjunct to her work with me on classical piano repertoire. What an eagle eye she had for consecutive fifths and octaves when correcting my Bach-style four-part harmonisations! I'd think I had made it through unscathed, but she'd look again and suddenly find them lying between the alto and bass or whichever voices, eagerly marking the forbidden constellations with her punitive pencilled signage. She also showed my compositions to Lovelock, who gave me much very valuable feedback in reams of handwritten notes. I don't know how it was that as a schoolboy I connected with such master teachers from the rather unprepossessing suburbs I moved in. I still visit Mrs Silcock, now in her nineties.

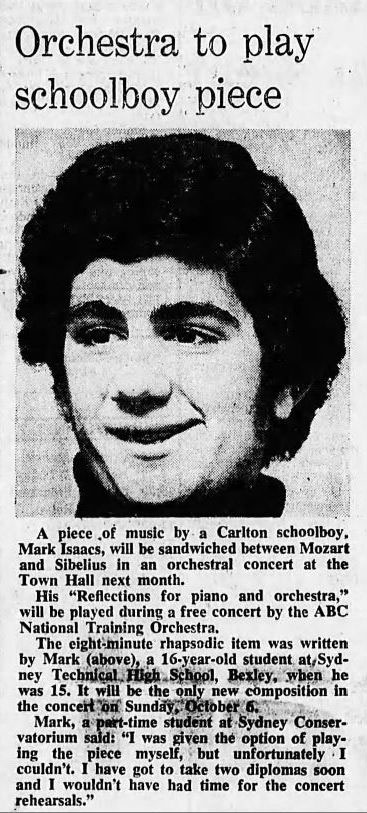

Mark Isaacs in an interview

(SMH 6 Sept 1974).

Click for a larger view.

At that time I also trotted off several times a week after school by train to the Conservatorium for classes in chamber music performance (where I encountered flautist Jane Rutter as a schoolgirl) as well as jazz arranging and ensemble studies. I put myself forward as a regular on the classical 'new music' scene in Sydney in the first half of the 1970s. James Murdoch, a doyen of the movement, noted to me with commendation that I was the only schoolchild regularly in attendance at classical 'contemporary music' events like Music Rostrum, one of his many brainchilds. Peter Sculthorpe took a typically warm interest in my schoolboy compositions - he would be another later formal composition teacher at University - and my school chum David Brown and I would take the train almost every weekend to Sydney Symphony Orchestra concerts at Sydney Town Hall (there was no Opera House then), the apotheosis of which was the 'Proms' which saw us all sitting on the Town Hall's floor, on picnic blankets or some such, to hear confrontingly beautiful contemporary classical music by Australian and international composers, often conducted by the late Patrick Thomas. It was certainly a vitally energetic time.

Along the way, still a schoolboy, I went to see anyone famous who would have me, to ask for advice about my compositions. Composer Eric Gross smoked a pipe, while turning through all the pages of one of my scores, and put forth the valuable admonition to be less 'four square', and composer Werner Baer, who worked in music publishing at Albert's, seemed to expect that I could play at the drop of a hat Chopin's frighteningly difficult first C-major etude (I can play it now, but not then).

My second piano-and-orchestra piece was played at Sydney Town Hall when I was sixteen, scarily followed in the program by none other than Sibelius, and preceded by Mozart. I had been invited, by the ABC, to play the piano part myself but declined, and I lied to the Sydney Morning Herald journalist who came to interview me that this was because I didn't have time to rehearse, having to take two diplomas soon. The diploma bit was true - I was taking my AMusA in both theory and piano at the time - but it wasn't really why I opted not to play. I could have found the time, but, as a composer, I wanted a real grown-up pianist to play my work! To me, a more accomplished reading of my piece was far more important than the limelight of being at the piano: I was then, as now, a composer first and foremost. As it happened, concert pianist Mark Davies, whom the ABC accordingly engaged, gave a rather lacklustre reading of what was admittedly juvenilia, and it occurred to me then, as an afterthought, that I should perhaps play the piano in public from time to time.

My final year in high school, 1975, was a watershed for many reasons. While still sixteen, I wrote what I could now call my Op. 1, since it moved rather beyond the more trivial clump of juvenilia that preceded it. It was a work called Interlude for flute and piano, somewhat inspired by Fauré, César Franck and Poulenc. I sent the score to the ABC, and they programmed it to be recorded for national broadcast by two distinguished Melbourne-based classical performers. However, it was a very rocky road getting to that point with the piece, traversing which has given me resilience I draw on to this day.

I did my scoring at home on a desk positioned under a window. On that fateful day I was almost to the end of writing up the score in black ink, and since it had a very thick and busy piano part it had taken all of my school holidays to get that far. While we were out, it rained, the wind blew the rain diagonally through the window that was left open, and upon our return my score was just a black, sodden blob. I was beyond mortified, and my mother, to her credit, while fully empathetic, provided some 'tough love' along the lines of pointing out that if I did no more than continue to feel sorry for myself, the piece would never be heard, and thus if I wanted it played, I had no choice but to knuckle down and do it all over again. Which I did.

Writing up long complex scores is very hard and gruelling labour, and this experience gave me much muscle for the relentless arduousness required of me in future, when I would in time grow a large callous on the middle finger of my right hand, put there by the pencil pressure of thousands of pages of orchestral and other scoring. Since 2003 I have only sketched in pencil, doing my actual scores on the computer (with, as you might imagine, multiple backups both onsite and in the cloud!). Though the finger callous has consequently subsided it has not disappeared entirely and remains a kind of composer's 'mark of Cain'.

Although the music teachers I had while at school were immeasurably important, I owe the greatest debt to Jim Black, the aforementioned English literature teacher of my senior high school years. From him I gained a firm value system that has mapped out my career path since.

Black (we called him 'Jock' because of his thick Scottish accent) was another Dead Poets Society Robin Williams figure. Like Leechman, normal class timetabling was woefully insufficient for his program. In our final year he announced that there would be further classes every day after school. These lasted an hour or so and he would then walk to the bus stop with us, still putting forth a steady stream of literary criticism. I can see him standing with a group of us even on the bus itself, hanging on for dear life to the roof stirrup as the bus lurched him from side to side, while still undauntedly providing for us - and indeed the rest of the passengers - further explanation as to what might have been going on in Ophelia's mind. As the final exams drew nearer, we were also summoned to his home every Sunday afternoon for further discussion on the texts, with accompanying home-baked cakes.

Whether it was Hamlet, Tess of the d'Urbervilles, sonnets by John Donne or poems by A.D. Hope, Jock Black seemed invariably to draw out the same underlying theme from each text: the individual strives to stand steadfast, remaining resolutely true to the noblest of values, as a beacon of spirit that resists the prevailing insidious societal forces of materialism and conformity. It's been said that the true purpose of reading literature is to craft a character and indeed change one's life, and it was clear that Jock was not teaching us literature at all, but trying to change our lives while using the texts as tools. He certainly changed mine.

in 2015 by Omega Ensemble, conducted by Isaacs.

I can thank Jock for instilling in me the conviction needed to make my most important life decisions, whether it be walking away from a promising career writing orchestral music for film and television because my artistic principles were too often under assault there, in refusing to seek out the security of music faculty positions in academia or having a steady stream of students come to the house, or not falling into prestigious artistic directorships for flagship organisations. It's his voice that told me to find a way to cut my cloth and live on less than the minimum wage for the last two decades as I have done, because that's what an artist does if it's what's necessary to hold to the values of real freedom and integrity.

Following school I spent ten mostly continuous years in undergraduate and postgraduate study as a classical composition major, with secondary studies as a classical pianist and conductor. Along the way I had some truly formidable mentors both here and overseas: Isadore Goodman, Peter Sculthorpe, Nicholas Routley, Sergiu Celibidache, Richard Toop, Igor Hmelnitsky, Michael Hannan, Gillian Whitehead, Brian Howard, Samuel Adler, Josef Tal, David Burge, Alexander Tamir, Lucy Greene, Martin Wesley-Smith, Robert Morris and Graham Hair. I thank them all for lighting up the path I began to walk half a century ago. It is my wish to continue upon it and produce music until the age of 112, thus giving a full century of effort to the work that Leechman ordered his 'bumptious prig' to begin to undertake at age 12. It is without a doubt a 'long game' and, indeed, should be: the first symphony I envisaged writing as a lad was not completed until my 55th year (commissioned by my former teacher Kim Williams). I've written two more since then, and, I think, have many more still in me.

AMC resources

Mark Isaacs - AMC profile (works, recordings, articles, events)

'Insight: Clock time, imaginary time and the Resurgence Band' - an article by Mark Isaacs on Resonate (18 November 2011)

Further links

Mark Isaacs - homepage (http://www.markisaacs.com/)

The Music Trust (http://musictrust.com.au/) - advocacy, articles, news, resources

© Australian Music Centre (2018) — Permission must be obtained from the AMC if you wish to reproduce this article either online or in print.

Comments

Be the first to share add your thoughts and opinions in response to this article.

You must login to post a comment.