13 June 2014

Australian music for the double bass - a personal introduction

Image: Jim Coyle

Image: Jim Coyle © Phyllis Wong - reproduced by kind permission of phyllisphotography.com

Composer and teacher Jim Coyle's research work at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music includes a survey of Australian music for double bass. He shares some of his expertise and findings in this article about some key works for the instrument.

Australian composers have shown a very wide variety of approaches to writing music for the contrabass over the past forty years. These approaches reveal an interesting microcosm of changes in musical style and compositional techniques in that time. The Australian Music Centre holds more than thirty works in which the contrabass is the solo instrument. These works include compositions by many (but by no means all) of our most significant composers. The development of musical style and language in this repertoire is reflective of most of the trends in Australian compositional practice in that time.

The collection includes seven works for contrabass solo with orchestra, four of which (works by Colin Bright, Mary Finsterer and two by Barry Conyngham) are concertos. The earliest of these is Shadows of Noh (1979) by Barry Conyngham, an avant-garde and experimental work. Conyngham's more recent concerto Kangaroo Island (2010) is considerably more conservative in its approach. Indeed, comparing two works of the same genre from opposite ends of a composer's creative output makes a very interesting study. Shadows of Noh is not only more adventurous in its artistic vision and musical technique than Kangaroo Island is, it also shows an almost obsessive attention to detail which is not present in the later piece. These two approaches are broadly indicative of the changes in Conyngham's style over the thirty years that separate them.

Lake Ice (2013) by Mary Finsterer is a concerto of imagination and subtlety, and its style contrasts quite strongly with much of Finsterer's previous output. The solo contrabass opens the work alone and immediately begins a delicate exploration of timbre which is a hallmark of Lake Ice. The opening figure

is a cell on which much of the opening and closing passages of the piece is based. The transformations to this and other themes are constant and subtle. Lake Ice is in a single, continuous movement but has the slower, more widely spaced music at the beginning and the end.

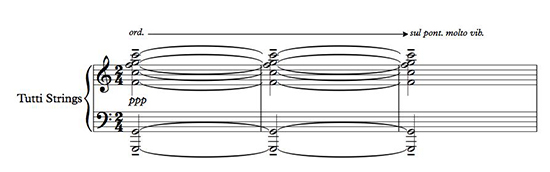

This use of extended techniques for subtlety and colouristic nuance, rather than for gestural novelty, is also followed in the orchestra. Icy, ethereal chords on string harmonics are given extra sheen and perspective by the addition and subtraction of orchestral colours such as bowed vibraphone and woodwind flutter-tonguing. This is a highly effective and imaginative way of colouring a musical line, creating a constantly changing timbral patina (e. g. bars 17-19 notated at concert pitch):

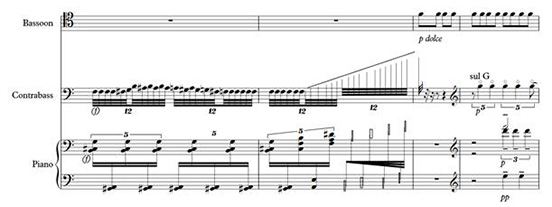

Another admirable characteristic in Finsterer's use of tone colour and instrumental technique is the way in which she nuances certain effects, gradually introducing them. These effects include gradually introducing tremolando, 'late shaping' of crescendos and moving the bow towards the bridge while increasing vibrato (e. g. bars 173-175, strings only shown):

One particularly striking feature of Lake Ice are the solo instrument's 'strange and beautiful' sonorities, particularly in its 'seldom heard' upper register. Finsterer makes very effective play of the contrast between the warmth of high arco notes and the glassy, icy quality of harmonics in the same register. This contrast is particularly telling on a solo contrabass (see, for example, bars 563-606 in the Lake Ice score).

There are playful qualities, too, in all the subtleties of Lake Ice; in its frequent use of triple rhythms and in the lightness of its textures. This playfulness is of great importance in works of this sort of imaginative scope, particularly in works which were inspired by the imaginations of children.

In 2010, Matthew Hindson composed Crime and Punishment, a relatively short concertante work for contrabass and string orchestra. It is wonderfully typical of Hindson's writing, in that it contrasts episodes of grimly loud dissonance with quiet reflective moments and passages of great rhythmic verve and vitality.

The above example, from bars 41- 43, is typical of Hindson's music in this mood. The rhythm has a clear straight-ahead four-to-a-bar feel, but has enough rhythmic sophistication to make it interesting as well as toe-tapping. Of all Australian composers, Matthew Hindson is the one who perceives and exploits the greatest amount of rhythmic edge out of the string instruments, a soundworld explored to the fullest extent in works such as Homage to Metallica (1993) and In Memoriam (2000). In some passages in Crime and Punishment, the colour and pitch of the notes is chosen to make it sound more like a drum kit solo than anything else (page 32, bar 166):

In Crime and Punishment, Hindson also uses the repetition of these ostinato figures with crescendo and thickening texture to build climax. These sorts of techniques clearly draw inspiration from popular dance styles of the twenty-first century. By dance styles I mean such things as rap, house, techno and so on. Hindson even manages to evoke the 'epic' sonority of the dance floor anthem in this work, thereby obtaining far more raw power from a string ensemble than seems possible (page 26, bar 185).

By drawing on these sorts of techniques (syncopated ostinato, four very clear beats to the bar, textural thickening by adding more layers of ostinati, rigid tempo) Hindson is making his a more international voice than many of his compatriots, because these styles are very much part of the compositional language of such composers as Thomas Ades (Asyla, 1997) and Steven Mackie (Turn the Key, 2006). However, these influences are much rarer in Australian compositions of note.

There are comparatively few chamber works which feature the contrabass prominently, and these tend to be extremely virtuosic works that rely on the remarkable technique of a particular player well-known to the composer. Examples of this type of piece include Peter Tahourdin's Dialogue no. 3 (1978), a duet, written for the world's leading proponent and practitioner of extended techniques for the contrabass, Bertram Turetzky and his flutist wife Nancy.

Andrew Ford's Pit (1981) was written for bassoon, piano and contrabass, and has been performed by the ensemble AustraLYSIS. The contrabass part is extremely demanding with rapid passage-work, extremes of pitch and dynamics and very quick changes between arco, regular pizzicato and Bartók pizzicato. One remarkable feature of Pit is that Ford integrates very new (at the time) extended techniques into an expectation of highly virtuosic playing of complex music. In other words, this work is not simply a timbral experiment, as some pieces in this repertoire are, but a piece of larger vision in which extended techniques are simply one of the elements.

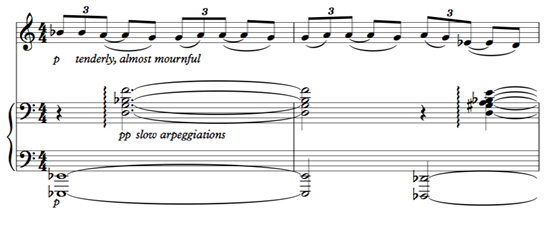

The largest category of solo music for the contrabass is that of solo pieces either unaccompanied or with a piano. Some of these works are highly virtuosic; others far more suitable for student players preparing examinations and recitals. Andrew Schultz wrote his seven miniatures Suspended Preludes in 1993. Each of these focuses on one particular extended technique on the contrabass; for example in the first movement, both bass and piano have pizzicato chords throughout, and the third movement is a study of piano and bass as drums. The exception to this is the fifth movement which is a world of original colour and gesture:

Dominik Karski takes this experimentation with colour further still in Along the Edge of Darkness (1999), as this example shows:

The example quoted above is for open strings only. There is a scordatura used throughout the piece. Even so, this is a highly complex gesture requiring very precise and detailed notation, particularly when one bears in mind the example above only lasts three seconds and is for a single unaccompanied contrabass. Technically and timbrally Along the Edge of Darkness is the most advanced contrabass piece by an Australian composer in the twentieth century, exploiting techniques that have hitherto been the preserve of specialist avant-garde composer-performers overseas.

Scherzo Alla Francescana (1990, revised 1994) by Claudio Pompili is almost a treatise on extended techniques for solo bass. Pompili is extremely ambitious in the demands he makes on his soloist in this unaccompanied work, and its single page contains a number of pioneering techniques. These include differing types of col legno bowing (scraping, striking, bouncing; with full wood or half hair/half wood). It also includes 'half harmonics' which have become fairly standard gestures in low string writing in recent years, but this is an early example. The strings are played towards the bridge, on the bridge (quite a dramatic difference in sound) and behind the bridge. There is even a quiet lyrical passage played behind the bridge. The tailpiece itself is even bowed in a recurrent gesture.

Scherzo Alla Francescana is also an early example of nuancing of string techniques. For example, an indication to move the bow gradually closer to the fingerboard during a passage is fairly commonplace now, but was innovative in the early 1990s. Indeed, one of the most significant developments in string writing in the past few years has been composers applying these 'dimmer switches' to techniques such as sul tasto, vibrato and even col legno.

More accessible works both for performer and listener include Burning (1997) by Houston Dunleavy. Burning is a dramatic showpiece for a bass soloist requiring formidable technique and a strong sense of bravura. Dunleavy keeps very close to the idea that he is writing for a string instrument and his thoughtful use of subtly different bowing and pizzicato styles maintains the listener's interest more convincingly than a series of apparently unconnected gestures could.

Frequently performed works (relatively speaking) include A Little Suite(1999) by Geoffrey Allen. It is quite typical of Allen's output in that its musical language is very much like that of British music of the mid-twentieth century, as is its approach to such things as mood and structure. Another such example is Binary Code (2010) by Richard Charlton. It is a light, appealing work that is interesting for its use of some extended techniques in a more popular music setting. It was written as an examination piece for a high school graduating student and has the mood and practical consideration to appeal to a young musician.

Matthew Hindson's Yandarra (1998) is one of the most popular and the most often performed piece in this entire repertoire. The work opens with some stormy, rough effects for bass alone. Hindson's use of the natural resonance of the instrument in this passage is very nicely judged and he makes telling and subtle contrasts of such effects as a G played on the G string then the D string, and a four note chord (containing three open strings) arpeggiated upwards and downwards.

The main body of Yandarra is based on a more lyrical theme based around a characteristically Hindson melodic motif.

There is a clear affinity between this melody and the themes of Hindson's teacher Peter Sculthorpe and, for that matter, the melodic shapes of Aboriginal song. One of the strongest aspects of the lyrical side of Hindson's music is that it sounds characteristically Australian whilst retaining its individual integrity. The piece goes on to explore the use of melodic seconds in a variety of moods and dynamics, and the altered unison on the note G from the opening passage also becomes an important idea.

Bassists who enjoy exploring the lyrical aspects of their instrument find works such as Yandarra particularly rewarding.

Interest in the contrabass among Australian composers continues to grow, encouraged by some fine players who are always seeking new work and by some excellent bass pedagogy of our younger players. The bass offers huge potential for composers; a lyrical voice to rival that of the cello and a capacity of a huge and subtle palate of extended colouristic techniques. My own recent works for the instrument (The Light Fantastic (2013), The Dark Fantastic (2013), On the Heaviness of Sorrow (2013), Billy Bray Abides in the Light (2013)) have explored the bass's great potential, and writing music for this instrument is intensely rewarding.

[Updated: 18 September 2014]

© Australian Music Centre (2014) — Permission must be obtained from the AMC if you wish to reproduce this article either online or in print.

Subjects discussed by this article:

- Concerto for double bass and orchestra by Barry Conyngham

- Pit by Andrew Ford

- Suspended preludes, op. 49 by Andrew Schultz

- Dialogue no. 3 by Peter Tahourdin

- Scherzo alla Francescana by Claudio Pompili

- Crime and punishment by Matthew Hindson

- Kangaroo Island by Barry Conyngham

- Along the edge of darkness by Dominik Karski

- Yandarra by Matthew Hindson

- Little suite for double bass and piano, op. 35 by Geoffrey Allen

- Burning by Houston Dunleavy

- Binary code by Richard Charlton

- Lake Ice by Mary Finsterer

Jim Coyle is a Sydney-based composer and teacher. He is currently undertaking research at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music which includes a survey of Australian work for the contrabass.

Comments

Be the first to share add your thoughts and opinions in response to this article.

You must login to post a comment.